JOHANNESBURG/NAIROBI, 4 June 2014 (IRIN) – As security forces in Kenya continue to round up and…

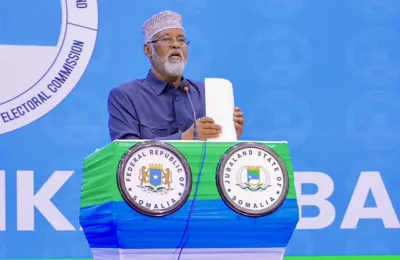

© Ahmed Hassan/IRIN

In late May, the Somali government pulled out of a meeting with UNHCR and the Kenyan government to formally launch a Tripartite Commission and discuss implementation of the Tripartite Agreement. The Agreement, signed in November 2013, outlines the procedures for the gradual and voluntary return of Somali refugees from Kenya, which is currently hosting around 423,000 Somalis holding refugee status.

The scheduled 27 May meeting was to be first of the Tripartite Commission and was expected to produce agreements on a number of joint actions, including the launch of a pilot phase of a voluntary returns programme that has been on hold for several months. The cancellation of the meeting stalls the dialogue on voluntary returns to Somalia where internal security is currently challenged due to a joint military offensive against the al-Shabaab insurgency by the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) and the Somali National Armed Forces (SNAF) in south-central Somalia. Recent estimates point to around 73,000 people being displaced due to the military offensive, including to some of the areas identified for voluntary refugee returns as part of the pilot phase.

Explaining its decision not to attend the meeting, Somalia cited “the detention and deportation of Somali refugees both documented and undocumented” which it described as contrary to the letter and spirit of both the 1951 Refugee Convention and “more importantly”, the Tripartite Agreement.

Kenya’s Commissioner for Refugee Affairs, Harun Komen, responded that Somalia’s decision not to attend the meeting was “unfortunate”.

“We are still committed to the Tripartite Agreement and Mogadishu must show it is committed as well,” he told IRIN. He added that most of those repatriated would return to the Somali region of Jubaland and that if the Somali government failed to move the process forward, “we have options including dealing with the Jubaland administration or doing it with UNHCR.”

UNHCR did not comment directly on Somalia’s last-minute withdrawal from the meeting but its representative for Somalia, Alessandra Morelli, noted that “The way forward is to ensure that there is a strong dialogue and discussions on all aspects of returns and reintegration in Somalia. The Tripartite Commission is the most important forum and initiative in place to ensure that voluntariness will guide refugee returns and that those wishing to return to Somalia can do so in a safe and dignified manner.”

Arrests and deportations

Since Kenya’s Interior Ministry launched Operation Usalama Watch in late March, purportedly as an anti-terrorism operation, more than 4,000 individuals are estimated to have been arrested and detained, most of them ethnic Somalis living in the Nairobi suburb of Eastleigh. A further 2,000 refugees have been sent to Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps while 359 Somalis have been deported to Somalia by air using chartered commercial airlines flying from Nairobi to Mogadishu since early April.

Usalama Watch follows a spate of attacks involving grenades and firearms in Mombasa and Nairobi in March. Such attacks have continued since the start of the operation, which came soon after the government announced that all urban refugees had to move to the remote Kakuma and Dadaab refugee camps, despite a 2013 high court order prohibiting such a move.

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), at least three of the recent deportees were registered refugees while many of the others may have had genuine claims to asylum but been unable to apply since Kenya stopped registering urban asylum seekers in December 2012.

Fowzia Hussein Da’ud was among those who had tried and failed to register as an asylum seeker in Nairobi and as a result was considered undocumented. She was detained by Kenyan police for 45 days before being deported to Mogadishu where she spoke to IRIN over the phone. “I am so demoralized that I have been separated from my two kids who are now in Nairobi with relatives. I can’t stay here in Mogadishu; this is the place where my husband was killed six years ago,” she said, adding that she would like to move to Uganda but cannot afford to.

HRW has said that the deportations constitute refoulement, a violation of a key principle of international refugee law that forbids the forced return of people to places where they risk persecution or serious harm.

Security concerns trump tough living conditions

Kenya has hosted large numbers of Somali refugees since the collapse of the Mohamed Siad Barre regime in 1991. Around 35,000 of the current caseload live in urban areas outside of refugee camps, while an unknown number of Somalis live in Kenya as undocumented migrants.

onditions in the Dadaab camps have deteriorated in recent years as insecurity and dwindling donor funding have severely impacted the ability of aid agencies to deliver services, and since the Kenyan authorities placed a moratorium on registrations of new refugees in October 2011.

Despite the presence of an internationally supported federal government in Mogadishu,

there is a broad consensus among aid agencies, including UNCHR, that large parts of Somalia are too unsafe to receive returnees. At the same time, some 2.9 million people are affected by a humanitarian crisis, one that has attracted just a fraction of the US$822 million needed to address it.

And on 2 June, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization warned that “late rains and erratic weather patterns in Somalia have raised concerns over a worsening of the food security situation, as food stocks from the last, poor harvest become depleted and prices continue to rise sharply.”

Somalia’s State Minister for Interior and Federalism Affairs Mohamud Moalim Yahye recently told the IPS news service that “the unplanned and uncoordinated deportation of people, especially the youth, will create chaos and anarchy as there are no resources to support and them create jobs for them.”

Through the pilot return programme, which has yet to launch, UNHCR is planning to provide return assistance for up to 10,000 refugees to three districts of South Central Somalia – Luuq, Baidoa and Kismayo – to where aid agencies including UNHCR have access. The return package will include a transport allowance and access to food and basic shelter items as well as assistance starting up livelihoods.

The relatively low numbers of Somalis returning home in the first three months of the year suggested that for the vast majority of Somali refugees, difficult conditions in Kenya were not enough to override deteriorating security in Somalia. Between January and March 2013, at a time when stability appeared to be returning to several parts of the country, nearly 14,000 Somalis crossed the border from Kenya.

During the same period this year, only 2,725 refugees made the journey, while less than 3,000 had visited Return Helpdesks in the Dadaab camps, according to UNHCR. Returns picked up slightly in April, as the crackdown by Kenyan security forces got underway, with 1,442 Somalis going home. These cross-border movements are believed to be largely temporary and in conjunction with rainy seasons and farming activities in south central Somalia.

Pushed to return?

UNHCR’s Voluntary Repatriation Handbook describes “the principle of voluntariness as the cornerstone of international protection with respect to the return of refugees” and stresses that a truly voluntary decision to return should be made in the context of both conditions in the refugee’s home country (‘pull’ factors) and conditions in the host country (‘push’ factors).

“As a general rule,” notes the handbook, “UNHCR should be convinced that the positive pull-factors in the country of origin are an overriding element in the refugees’ decision to return rather than possible push-factors in the host country.”

Article 10 of the Tripartite Agreement also states that the decision of refugees to repatriate to Somalia “be based on their freely expressed wish”. UNHCR’s Morelli added that “external push factors, which may jeopardize the right of the refugees to make voluntary (and informed) decisions about their returns to Somalia, should be avoided.”

However, several refugees that IRIN spoke to said constant harassment by the police since Operation Usalama Watch began and the fear of deportation had forced them to consider returning to Somalia.

“I am moving back to Mogadishu at a time the security situation is still chaotic, but I have no other option,” said Abdirahman Mohamed Jama, 42, who works at a Somali radio station in Nairobi and has lived in the capital with his wife and four children since 2008.

“The police have come to our flat a number of times, and after showing them our refugee documents, they handcuffed me and my wife and threatened to take us to the police station [unless we paid a bribe]. We paid them several times, but we cannot afford to continue paying them. We are in shock, fear and suffer from many sleepless nights,” he told IRIN. “I have to leave Nairobi before I am forcibly expelled to Somalia or separated from the rest of my family as has happened to many of my Somali neighbours.”

Rufus Karanja, a programme officer with the Refugee Consortium of Kenya argued that “the manner in which operation [Usalama Watch] has been conducted has created a negative push factor” that was causing some Somalis to opt to return home rather than endure continued harassment, extortion and arbitrary arrest.

“In our view, this may actually amount to induced forced return, something which goes against the spirit and intent of the Tripartite Agreement which provides that the return of Somali refugees should be voluntary and conducted in safety and dignity,” he told IRIN.