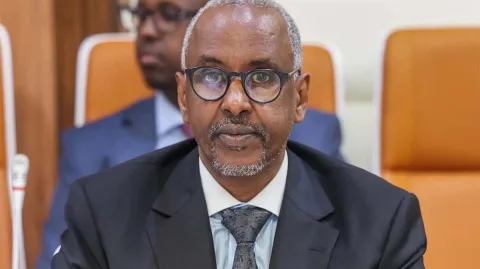

Speech by Nuradin Dirie at the Centre for African Studies. University of Copenhagen. Mr Chairman, It…

Speech by Nuradin Dirie at the Centre for African Studies.

University of Copenhagen.

Mr Chairman,

It is a great pleasure for me to be here today in the University of Copenhagen – the largest learning institution in Denmark. Up until recently, my exclusive knowledge and what I know about Denmark was limited to my former boss, Christian Balslev-Olesen, who is sitting with us here today. But since then, I have learned quite few things about Denmark.

For exmple, I was made aware that the Danish flag is the oldest national flag in the world. According to one Danish friend of mine, the flag fell from the sky during the battle of 1215 leading to Danish victory. My friend did not tell me who you were fighting at that time, but today, I can only wish that something will come down from the sky on Somalia in order to get the country out of the mess and madness which it is in.

I learned that the Danish people have been very generous to my people. Over the years, and since the fall of the Somali state, Denmark has opened its doors to Somalis as they fled conflict and insecurity in search of safety. They settled here and despite triumphs and tribulations, 20 thousand Somalis are now citizens and residents in this great country contributing to its national life.Â

Danish generosity also reaches Somalia itself. Denmark is today one of Somalia’s main donors and in the last 5 years alone, has contributed about 40 million USD to support humanitarian work which has benefited vulnerable Somalis in times of drought, flood and conflict emergencies.

Before I talk about the cost of the state failure, I would like to say a bit about the state that we had in Somalia prior to its collapse. Our experience with modern statehood – the recognised system by the international community of states – is 49 years old. Within that system and within that relatively short period, we had 9 years of multiparty democracy, 20 years of military dictatorship and 20 years of anarchy.

While on one hand, international recognition of the Somali state is relatively new and chaotic; on the other Somalia itself is the product of many years of human history and human relations including 100 years of colonial history and several centuries of pastoral democracy.

We have had mixed experiences with our different governance systems in the modern Somali state. During the democratic period we enjoyed peace, security and rule of law. The freedom of expression we enjoyed was second to none in Africa: so much so, that during that time Somalia did not have a single political detainee – a novelty in Africa that time. That experience of freedom and democratic values was not only short lived but superseded by one of the most repressive and predatory regimes the world has ever seen.Â

The contrast could not have been greater. We went from almost complete freedom into a level of control that could only be described as paranoia. The military regime in Somalia terrorised the population. It made things like gossip a capital crime. People disappeared after being accused of gossiping against the revolution. That military regime set the stage for Somalia to become unique in the history of the modern world as the only country that was, and continues to be, a failed state for two decades.

In 2009, Somalia is still no nearer to forming a functioning central state than when it started to disintegrate in 1991.

Since 1991 the United Nations Security Council has adopted 43 resolutions about the situation of Somalia. This resulted in 15 attempts of internationally driven state-building processes, two international peace-keeping operations and a cost of 8 billion US dollars.

The current Transitional Federal Government is the latest attempt to establish the Somali state. Unfortunately, the government is severely challenged. The civilian population is trapped between the armed opposition on the one hand and the international and Somali forces on the other.

The human cost is great indeed. Since the collapse of the Somali state, one million people in Somalia died as a consequence of war, famine, and disease – a profound human tragedy. And as I speak, today we have 1.5 million people who are displaced within the country. They are essentially refugees in their own country. Somalia has the highest levels of malnutrition in the world with up to 300,000 children acutely malnourished annually. In fact, nearly 4 million people are now in what the UN calls, ‘humanitarian crisis’ – basically going to bed hungry every night.

The fighting is also depriving civilians of basic services such as health, because medics can’t reach people and people can’t get to hospitals. Pregnant women often spend days trying to get to a hospital because there are no health facilities nearby where they feel safe. Many are still travelling when labour starts and a number have died, along with their unborn children, because they couldn’t reach help in time.

But what is more disconcerting is that the insecurity in the country today has created treacherous conditions for aid agencies trying to deliver live-saving services. Indeed Somalia is the most dangerous country in the world for humanitarian aid workers. Last year one-third of all humanitarian casualties worldwide occurred in Somalia.

In combination, the grave needs of the people on the ground and the inability of the humanitarian community to access and assist them have created the most challenging humanitarian crisis in the world. Â

It is well established that, conflict and security are intrinsically linked to development processes. In addition to the human cost, the instability in Somalia continues to produce worrisome statistics which make the future prospect of development even bleaker.

· Things like the child and maternal mortality – among the highest in the world

· Access to clean drinking water – only a third of the population has it

· Only one in three children that survive, will attend primary school

· An average life span of only 47 years

Somalia is not facing the consequences of the conflict on its own. The whole region is now very embroiled in the troubles.

Ethiopia has always meddled in the politics of Somalia. It is not difficult to imagine why. About one-fourth of its land area in south-eastern Ethiopia, known as the Ogaden and Haud, are inhabited by the Somali people. The two nations have a long standing history of conflict.

But its involvement culminated in an invasion of Somalia in early 2007 under the pretext of security and as part of the global war on terror. I remember very well, prior to the invasion, all analysts and observers of Somalia warned against such move. They also predicted the grave consequences would come out of it.

But the invasion went ahead with the support, blessing and financial underwriting of big powers. The conflict which followed the invasion was marked by numerous violations of international humanitarian law. The human rights violations were such that ‘Human Rights Watch’ described Ethiopia’s military actions as ‘war crimes’. Despite huge human, diplomatic and financial cost, none of the stated objectives of the invasion were achieved.Â

Somalia today is a much more dangerous place for Somalis, for the region and for the rest of the world than it has ever been.

Ethiopia withdrew from Somalia in late 2008 and left a trail of destruction, devastation and a huge amount of anger. Ethiopia now has a standing army on its side of the border and the conflict has followed it inside the country itself.Â

Eritrea also used the opportunity to cause more trouble for its arch-enemy and is now very much involved in the conflict in Somalia as a proxy war against Ethiopia. It is arming and advising insurgents, facilitating transfer of finance to them and is committed to see this conflict escalate further.Â

Kenya, which for very long time managed to stay away from the troubles in Somalia, is very involved now and almost its entire military and security apparatus is geared towards defending potential incursions from the south of Somalia.

Djibouti, which was for very long time described as the island of tranquillity in that troubled region, is for the first time receiving direct threats from Somalia’s Al-shabab group.

The United States is very much involved too. It is hunting down suspected terrorist individuals, identifying them and bombing them with all the consequences.

The huge anger after the Ethiopian invasion released a combination of nationalism and radicalism that no doubt radicalised a significant number of the population. So much so that for Al Qaeda and its networks, Somalia – in which had relatively little hold before 2007 – has very much become one of its key bases.

But most alarming of all, is that the anger has reached Somali youngsters in the west. To the point that a number of them have left their homes in London in UK and Minnesota in the US to be part of the Somalia conflict. These are young people who, as children, were taken from Somalia under traumatic circumstances in order to give them a better life, free from conflict. The fact that they are now returning to Somalia to kill and be killed is for me, one of the most painful costs of the conflict in Somalia.

As far as I understand, Somali youngsters leaving the west to join the fighting in Somalia has not been a significant issue here in Denmark. Hopefully the individual cases that were reported from London and Minnesota are just a passing phase that will just fade away. But these are indicative enough to illustrate how a conflict in one remote part of the world can, indeed, have global ramifications.

Perhaps nothing demonstrates this better than the piracy off the coast of Somalia that has become a menace to the global maritime community. In 2008 alone, the International Maritime Bureau recorded 111 pirate attacks off the Horn of Africa.

Almost every nation was affected by these piracy attacks in 2008 either in vessel hijackings or increased prices for oil and other goods as a result of increased insurance premiums and the costs related to risk and security precautions. Others have increased their costs by travelling around the Cape of Good Hope in order to bypass the long Somali coastline and so avoid the pirates. According to Rand Foundation, the overall annual cost of piracy to the maritime industry is estimated to be between $1 billion and $16 billion.

The scale of these costs as a direct collapse of the Somali state is all too evident when one considers that Somali pirates can potentially impact on some 33,000 ships that transit the Gulf of Aden annually, including some 6,500 tankers which carry seven percent of the world’s daily oil supply.

It is to address that potential scale of disruption that the UN Security Council quickly issued four resolutions in 2008 to facilitate an international response to piracy off the Horn of Africa. It has triggered the deployment of perhaps the most eclectic and diverse armada of naval firepower ever assembled. And yet, despite the naval force of some thirty nations, the military presence has been unable to deter the attacks.

The failure of these counter-piracy operations reinforces that the reestablishment of government authority in Somalia is the only guarantee that piracy will not persist or re-emerge as a threat.

It is indeed true that we live in world where everything is globalised. Instability anywhere can translate into instability everywhere. The cost of state failure in Somalia has been extremely high in human terms, diplomatic terms and in terms of regional and global trade and security. We cannot afford to stand by and watch as another generation of Somali human potential is so pointlessly wasted.

Although the solution of Somalia starts and ends with Somalis, the outcome in Somalia will affect us all in one way or another. Like it or not, we all have a stake in seeing a stable Somalia.

And we should view the resilience and resourcefulness of the Somali people as characteristics which, if supported, can build a secure democratic state. But it will take sustained efforts to support the establishment of public governance systems in a country where half the population has never known peace or civil service structures.

It will take consistent global commitment and financial resources to make this happen. I hope we will all contribute to make it come about. If past evidence is anything to go by, it is our collective human capacity that gives me hope for Somalia and for the rest of the world.

Thank you very much

Nuradin Dirie

Nuradin Dirie is an independent analyst specialising in the Horn of Africa with particular interest in Somalia. He was former presidential candidate in Somalia in 2009 Puntland Elections and also served as senior special advisor to the United Nations.