By Katie Kuschminder, Davide Bruscoli, Andrew Pinney, Chris Barnett, Michael Loevinsohn, and Alex Thomson Increasing land…

By Katie Kuschminder, Davide Bruscoli, Andrew Pinney, Chris Barnett, Michael Loevinsohn, and Alex Thomson

Increasing land and sea controls and conflicts along key migration routes from East Africa have made migration from this region more dangerous. Many migrants headed for Europe, the Middle East, or southern Africa have become stranded in transit countries such as Libya, Djibouti, or Tanzania, making them highly vulnerable to being abused, deprived of their rights, or subjected to what multiple organizations have described as crimes against humanity. For reasons beyond their control, these stranded migrants cannot continue on their journey, are unable to turn back, and are stuck in potentially dangerous situations where they may be assaulted, kidnapped, or even die.

In such circumstances, receiving assistance for return to one’s origin country from a government or international organization can be lifesaving and, very often, the only way out of detention, destitution, or other challenging circumstances. Moreover, many stranded migrants return penniless. Their families may have incurred significant debts to finance the migration, and their return often dashes relatives’ hopes to repay these debts, furthering many returnees’ feelings of hopelessness. Economic assistance can help returnees start small businesses, and counseling can help ensure those businesses thrive. Furthermore, psychosocial and medical assistance can smooth re-entry for migrants who may feel ashamed, isolated, and traumatized from their journeys.

This was the case for many migrants assisted by an initiative funded by the European Union’s Emergency Trust Fund for Africa and implemented by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), called the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration. The joint initiative spanned three programs implemented between 2017 and 2023 in 26 African countries across the Horn of Africa, North Africa, and the Sahel and Lake Chad region. IOM provided three-pronged assistance: migrant protection through facilities in key transit points providing immediate protection and assistance to migrants, known as Migrant Resource Centers; facilitation of return; and provision of reintegration support after return based on a case management approach, sometimes over a prolonged period. With a 603-million-euro budget, the initiative assisted the return of more than 134,000 individuals and reintegration of 124,000, making it one of the largest return and reintegration initiatives ever undertaken to protect African migrants from extreme situations of abuse and vulnerability and guarantee their return.

The initiative was unique in the size and scale of the multilateral funding, in its status as the first program to focus on return and reintegration from stranded migrants within Africa, and also because it delivered the first large-scale impact evaluation on reintegration. Although reintegration programs have become common over the past 20 years, there has been little rigorous research on their effectiveness. With the ending of the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, the initiative concluded in 2023.

This article draws from data and the authors’ analysis evaluating the EU-IOM Joint Initiative in the Horn of Africa to illustrate some key experiences faced by returnees assisted under this program. It offers evidence on the effectiveness of the assistance they received in its three main countries of operation: Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan.

Stranded along the Journey

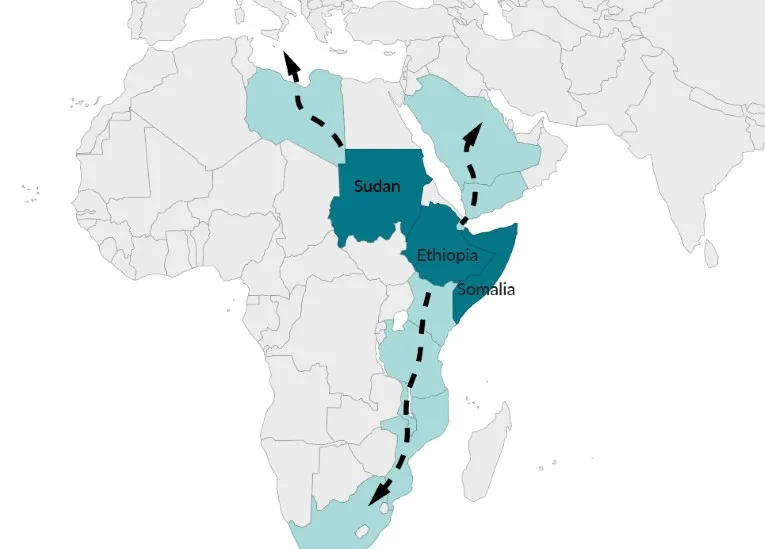

There are three main migration routes from East Africa (see Figure 1). The first is east, through Djibouti, across the Sea of Aden to Yemen, and ultimately to Saudi Arabia or, to a lesser extent, other Gulf countries. This route is highly dangerous due to the deserts, sea, and the conflict in Yemen. The second is south, towards South Africa, by sea or land routes often through Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique. Increased border controls along this route have made it more dangerous as well. The third route, and perhaps the most well known, is north towards Europe, with Libya being the most frequent country of transit. In Sudan and Somalia, the majority of returnees under the EU-IOM initiative had been stranded in Libya, whereas in Ethiopia the majority were stranded along the eastern route; the southern route and lastly the northern route followed.

Migrants are considered stranded when they have no ability to continue their migration onwards to their intended destination, have no resources for return, and for reasons beyond their control have become stuck in transit. In some cases, stranded migrants are unable to leave their current country, such as those in detention. Others are unable to go back the way they came, such as those who spent weeks crossing the desert. Migrants stranded along these routes face difficulties including physical exhaustion, violence or abuse, sexual assault, and economic or labor exploitation.

Crimes against humanity—including arbitrary detention, rape, enslavement, torture, and murder—have been documented against migrants along these routes by organizations including the United Nations. Following the European refugee and migration crisis of 2015 and 2016, EU policies and a migration control agreement between Italy and Libya have provided funding to Libyan authorities to prevent irregular migration to Europe. These interventions reduced the number of irregular arrivals to Italy to a recent low of 11,500 in 2019, however the nearly 157,700 arrivals in 2023 were the highest since 2016 (when 181,400 arrived) and surpassed 2015 levels (153,800). At the same time, the European Union has also invested in protecting migrants stranded within Africa, with the EU-IOM programming being an important element. The European Union is the primary funder of the Voluntary Humanitarian Returns from Libya program, which provides emergency return to stranded migrants’ country of origin, often from detention centers.

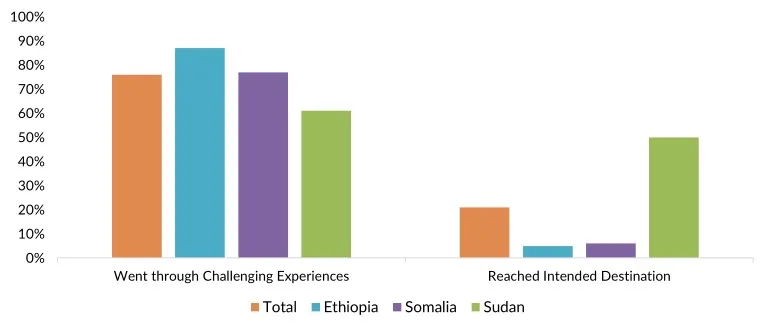

According to IOM, the migrants assisted by the EU-IOM program were considered to be vulnerable and not representative of all returnees to these countries, such as those returning from Europe, Saudi Arabia, or elsewhere via an assisted voluntary return program. Eighty-eight percent of those assisted by the EU-IOM program were men and the average age was 30. In a survey conducted by IOM with 1,148 returnees assisted by the joint program, most reported having gone through challenges during their migration journey that negatively impacted their well-being (see Figure 2). Approximately four-fifths said they had been unable to reach their intended destination, meaning the vast majority had been unable to work or earn money. The exceptions were mostly Sudanese migrants returned from Libya, who had been able to work there before crises occurred that often severely affected their livelihoods and assets. Most of the highly vulnerable returnees surveyed arrived in their origin countries distressed and without any resources.

In interviews, most migrants whose return was facilitated by the joint program expressed relief to have an option to get out of their current situation and return to their origin country. As one Somali returnee said, “After suffering and starving, the best thing was to come home where we felt loved.”

Return and Reintegration Experiences

After arrival in their country of origin, returnees most often felt relief or apprehension. One returnee in Ethiopia explained, “Within the first month of my return, I would assess my overall well-being at that moment as [at the highest level], as my family were highly happy that I had returned alive.” There is often significant relief to have survived and be back in an environment of safety with one’s family.

For others, however, return was more challenging. Some young men left without telling their families; others were kidnapped and had their families extorted to pay for their release. Some families incurred significant debt, including selling property or other assets, to pay for the release. Fifty-five percent of Ethiopian returnees reported migration-incurred debt, with lower numbers in Somalia (38 percent) and Sudan (36 percent). Families were rarely informed ahead of time about their loved one’s arrival, which often came as a shock. Many families needed to reconcile the financial loss while also helping the returnee cope with trauma. “They come back changed a lot, they suffer from nightmares, extreme stress and depression,” one mother in Somalia said. “He also felt that he did not reach his goals and felt guilty coming back. He did not talk to his former friends or the family members for around two months.”

Some returnees felt deep shame that their families had gone into debt or were significantly worse off than prior to their migration, which negatively impacted their well-being. One Ethiopian returnee stated, “I was struggling with my health and even lost weight as I was overthinking or worrying about how to support my father to recover from the economic bankruptcy he was in as a result of financing my migration.” As other research has confirmed, family debt may be significant and often plays a central role in returnees’ reintegration process; many struggle with shame at having been unable to reach their destinations and support their families from abroad.

Reintegration Supports

IOM provided supports to assist economic, social, and psychosocial reintegration. Upon arrival or during the first months after return, reintegration assistance focused on immediate needs and included temporary housing, transportation, pocket money, and near-term medical and psychosocial aid, as well as training sessions for starting and growing a business. Further reintegration assistance was then provided to support longer-terms outcomes, sometimes several months after return, tailored to individuals’ needs, as determined through counselling. This could include support for entrepreneurial microbusinesses, medical referrals, educational aid, housing, or technical and vocational education training.

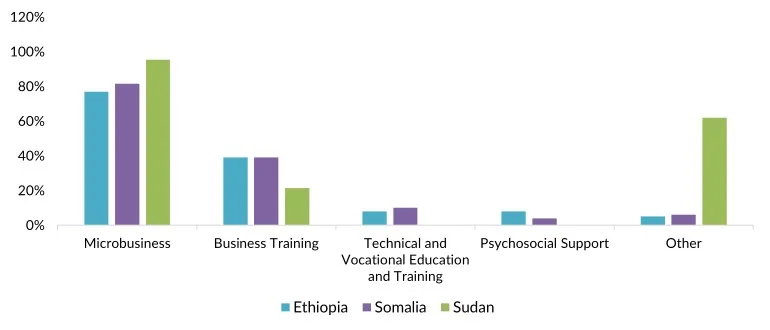

In all three countries, owing to migrants’ primarily economic drivers, microbusiness assistance was the most common service provided to returnees (see Figure 3). Many received a grant generally ranging from U.S. $1,100-$2,650 per individual, either in kind or in cash, to establish a small business based on a plan developed with a caseworker’s support.

Impacts of Assistance

Based on IOM’s Reintegration Sustainability Index, which uses 31 indicators to measure economic, social, and psychosocial reintegration, returnees receiving microbusiness support showed significant improvement in their overall reintegration in Ethiopia and Somalia. In Sudan, the index showed no such correlation, possibly due to the deterioration of the country’s economic and political situation in the run-up to the civil war that began in 2023.

Compared to nonmigrants with similar demographic characteristics in the same communities, returnees generally demonstrated successful outcomes one year later. In Ethiopia, data show that returnees’ reintegration reached a level statistically similar to nonmigrants more than one year after return, with evidence that some of this improvement is attributable directly to the reintegration assistance. Somali returnees eventually exceeded their nonmigrant counterparts’ index scores. Sudan is a unique case, since returnees immediately after arrival recorded a higher index score than nonmigrants; returnees’ level of reintegration did not change over time, but index levels among nonmigrant counterparts declined.

In Ethiopia, 31 percent of returnees had not yet received reintegration assistance at the time of survey, due to delays, enabling a comparison with those who did. Overall, returnees who did not receive assistance were significantly worse off than returnees who did. The stories of two individuals—Mesfin and Mulugeta—illustrate this difference, although they may not be representative of all cases.

Mesfin (pseudonyms are used to protect individuals’ identities) had been working as a daily laborer and decided to migrate in search of a better life. During his migration, his broker abandoned him in the desert, where conditions were harsh and he lacked shelter and sufficient food and water. He witnessed three other migrants die, experiences that still caused him pain. When he finally arrived in Djibouti after 75 days in the desert, he went directly to a Migrant Resource Center and was told he could be helped to return to Ethiopia. After everything he had endured, he was glad to accept the offer. Upon arrival in Addis Ababa, IOM gave him 2,000 Ethiopian Birr (approximately U.S. $35) and said he would receive additional assistance. At the time of his interview, Mesfin had been waiting for at least one year and had not yet received additional support from IOM, however was still hoping for it. He resumed working as a daily laborer, but his earnings were insufficient to provide for daily needs. With IOM’s assistance, he was planning to breed cattle. He rated his well-being as very low due to his poor economic position.

In contrast, Mulugeta’s reports of low overall well-being post-return changed once IOM support appeared. Mulugeta reported difficulty finding work after his return. “My family [was] also upset with me because I forced them to sell their oxen and spend on my migration.” Then IOM helped him. “In late 2019, IOM opened a shop for me. I began to believe that my life could change after that. I can therefore rate my well-being as good, as I feel good after the opening of the shop.” At the time of the interview, the shop was doing well and he hoped to expand the business. Mulugeta was positive and attributed the improvement fully to the IOM support.

As this comparison shows, it is quite difficult for returnees in Ethiopia to re-establish themselves and create a livelihood without assistance.

Follow-up on returnees is challenging, however, the survey findings suggest that few returnees in Ethiopia and Somalia have sought to remigrate. At the time of survey, only a small minority of returnees expressed that they would likely migrate again from Ethiopia (3 percent) and Somalia (2 percent). In Sudan, returnees were more likely to seek to migrate again (35 percent of respondents), which reflects that the worsening conditions in the country have hampered reintegration efforts significantly. Remigration intentions do not necessarily translate into actual remigration. In fact, anecdotal evidence suggests that this option is severely limited among returnees coming from a negative migration experience, sometimes resulting in involuntary immobility.

Psychosocial Reintegration Support

Researchers and programs increasingly recognize the importance for successful reintegration of some form of access to a social worker or psychologist. However, access to individual sessions is rare. Group psychosocial support, which can occur in group theater or information sessions, is far more common.

In the EU-IOM program, these types of sessions were provided in Ethiopia and Somalia and were found to be highly important for returnees. One Somali returnee from Libya stated, “It’s been extremely beneficial to me because when you think you’ve been through a bad situation, someone else has had a worse experience, and you’re like, ‘Oh, nothing happened to me, compared to the other guy’s challenges.’” Returnees might not discuss their migration experiences with family or friends, but these types of sessions allow them to relate their experiences to others. At the same time, the psychosocial assistance provided was often not enough for all returnees, and many respondents still struggled with their mental health.

Furthermore, returnees in Somalia reported facing stigma. One, Yasir, said he struggled with negative community perceptions of returnees and felt that his neighbors treated him differently upon his return. “People don’t always believe in you when you return from migration,” he said. “They think that ‘If I lend him money or give him something valuable, he’ll migrate again.’” Yasir said he felt he was treated differently as a returnee and was perceived as having wasted money, making it difficult to be treated the same as before. Yasir said he felt this stigma daily and did not have the same opportunities as peers who did not migrate.

Data collected on returnees assisted by the EU-IOM program highlighted the strong relationship between economic and psychosocial reintegration; economic success was correlated with psychosocial well-being. At the same time, it was important for returnees to have a certain degree of psychological readiness to fully benefit from economic reintegration assistance and navigate the challenges of running a successful microbusiness. This signifies the benefits of providing economic and psychosocial reintegration assistance in tandem.

Current Context: Shifting Dynamics in East Africa

The EU-IOM joint initiative ended in April 2023 following the end of its funding mechanism, the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, which had prioritized return and reintegration. Since then, EU funding for return and reintegration in East Africa has been increasingly focused on migrants traveling the northern route, discontinuing an important resource for assisting those headed places other than Europe.

At the same time, return and reintegration dynamics in the region have become increasingly complex. The conflict in northern Ethiopia and the civil war in Sudan have increased regional instability and led to a suspension of returns of stranded migrants to unstable regions. As a result, stranded migrants have had extended stays in Migrant Resource Centers as they wait for return. U.S. funding has consistently supported assistance for migrants stranded along the eastern route, although it has not included reintegration components following return. As this research has shown, reintegration assistance can significantly improve returnees’ livelihoods and well-being. Without it, returned migrants face continued challenges and a diminished ability to reintegrate.

Lessons Learned from Reintegration Approaches for Stranded Migrants

Increasing border controls and externalization of migration policies suggest that the number of migrants stranded in African transit countries may continue to increase or remain significant. Interventions to assist migrants in desperate situations—including by providing return and reintegration assistance—are important. Upon return, stranded migrants need support to be able to reintegrate and rebuild their lives.

The EU-IOM program in East Africa has shown that this assistance was generally greatly appreciated by returnees. Importantly, it could function as a humanitarian response that helped stranded migrants escape dangerous situations. Some had no one in their family or community who could have helped them return, and several faced dire conditions.

Results showed that economic reintegration support had the largest impact on returnees. Psychosocial support could also be significant, but economic assistance and having a successful microbusiness were the most important factors in successful reintegration. The country context is important, with the civil war in Sudan likely contributing to reintegration support being less impactful there than in the two other countries.

Future programs could consider how to ensure families are informed in advance of a migrant’s return and incorporating relatives into reintegration supports. Debt resolution pathways could also help to ensure reintegration can be sustainable. Timely delivery of assistance by identifying and progressively removing sources of delay would also help. And returnees’ agency could be supported by adapting assistance to often rapidly changing conditions.

As long as there are migrants stranded on their journeys, assistance will be needed to help them return to their origin countries and reintegrate sustainably. The EU-IOM program proved effective in key regards, and future efforts would benefit from learning from its experience.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IOM. This article is based on research and evaluation produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union.

Sources

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2024. Inner Journeys: Mental Health and Psychosocial Perspectives on the Migration, Return and Reintegration Experiences of Ethiopian, Somali and Sudanese Migrants in Vulnerable Situations. Nairobi: IOM Regional Office for East and Horn of Africa. Available online.

—. 2024. Returning Home: Evaluating the Impact of IOM’s Reintegration Assistance for Migrants in the Horn of Africa. Nairobi: IOM Regional Office for East and Horn of Africa. Available online.

—. N.d. About the EU-IOM Joint Initiative. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for East and Horn of Africa. N.d. IMPACT Study. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Mediterranean Situation: Italy. Updated June 23, 2024.