BAIDOA, 28 May 2014 (IRIN) – Acting governor of Baidoa and Sector 3 commander of the…

© Guy Oliver/IRIN

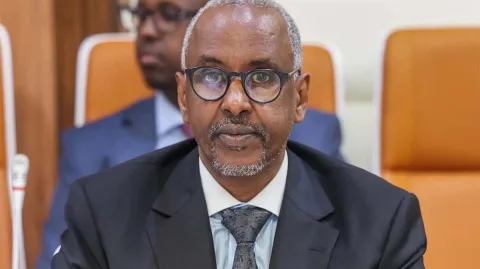

BAIDOA, 28 May 2014 (IRIN) – Acting governor of Baidoa and Sector 3 commander of the Somali National Army (SNA) Brig-Gen Ibrahim Yaro breaks into a broad grin, bordering on a chuckle, when asked whether his forces have any of their own helicopters.

“You see that vehicle,” he said, pointing to a pick-up truck with a 14.5mm heavy machine-gun mounted on the back, “that is the heaviest weapon we have in the sector [covering the Bay, Gedo and Bakool regions]. It’s borrowed from one of the clans. It’s on loan for free, although we [SNA] have to fix any mechanical problems. But they [the clan] can take it back any time they want to,” he told IRIN.

The national army’s dilapidated Baidoa barracks has a single coil of razor wire for a roadblock at its entrance – in stark contrast to the adjacent heavily fortified African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) base, which houses Ethiopian, Burundian and other soldiers from African states, as well as a small contingent of US special forces.

Any SNA personnel entering the AMISOM complex have to hand over their weapons – if they have any – to AMISOM guards.

Dress code for SNA troops is all but non-existent, with some personnel wearing civilian clothes and others a variety of military uniforms. Three SNA officers sitting a few metres away are dressed in camouflage gear. One has a Chinese uniform, the second a Turkish and the third a US uniform.

“It’s true we [SNA] don’t have uniforms and we don’t have enough ammunition,” said Yaro. “An AK-47 has 30 bullets in a magazine for each soldier. If someone has eight magazines is it possible to fight with him?

“Al-Shabab has more ammunition than us. AMISOM is not ready to give us more”

“Al-Shabab has more ammunition than us. AMISOM is not ready to give us more. If the SNA had more ammunition we could do more activities in the area,” said Yaro, a one-time soldier with ex-president Mohammed Siad Barre’s army.

SNA is being groomed to become the mainstay of the country’s security apparatus but remains a junior partner to AMISOM. The 2012 National Security and Stabilization Plan (NSSP) provided a blueprint for the rebuilding of Somalia’s security forces. It envisaged 28,000 professional soldiers and 12,000 police at a cost of about US$160 million over three years, including a reformed judiciary. The 2013 Somalia Conference in London also ranked security as the priority for resurrecting a two-decade-old failed state; European donor nations pledged more than $100 million for the security sector.

The US State Department said in a March 2014 statement that the US had provided more than $512 million in financial support to AMISOM since 2007, and a further $171 million for the development of an “effective and professional Somali National Army.”

UNSOA support

In January 2014 the UN Support Office for AMISOM (UNSOA) began providing “non-lethal support to SNA units in front line operations with AMISOM,” Markus Weiss, UNSOA’s coordination and planning officer, told IRIN by email.

After the fall of Barre in 1991 and the disintegration of one of Africa’s largest militaries of the time, Somalia experienced a military vacuum which ushered in the era of the warlords. Its military was first reformed in 2000 by the Transitional National Government (TNG) and then again by the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in 2004.

“The [UN 2013] resolution limits UNSOA’s support package to the provision of six items or services (food and water, fuel, transport, tents and medical support). The support is subject to conditions, like registration and vetting of SNA troops, compliance with UN policy on human rights, mandatory training on others,” Weiss said.

“So far, UNSOA has supported 3,600 SNA [personnel] in Sector 3 and 1,000 SNA in Sector 4 for training purposes only. Once the training is completed, we expect these troops to engage in joint operations with AMISOM. In Sectors 1 and 5 we are about to start the training while we wait for confirmation from SNA on support to Sector 2. In total, a maximum of 10,900 SNA troops will be supported in the first 12 months.

“It is still in the early stages of UNSOA’s support to SNA, but we expect this project to gather pace in the second half of 2014,” he said.

Clan loyalty

Yaro dismisses any suggestion that clan loyalties among SNA personnel, or poor pay ($100 a month plus $30 for food – stipends provided by the US and Italy), impede the operational readiness of his soldiers, but it is a view not shared by their military partners AMISOM.

“Clan loyalty is a big problem. SNA [operations] are restricted by clan influence. The police is especially clan-based, although the army is a little better. The SNA leadership is also very weak,” Col Gebrehaweria Fitwi, the Ethiopian force civil-military coordinator in Sector 3, told IRIN.

“Clan loyalty is a big problem. SNA [operations] are restricted by clan influence”

There are eight SNA battalions in Sector 3: four based in Baidoa, and two each in Bakool and Gedo. A battalion is considered the smallest military formation capable of independent operations – provided they have the necessary equipment – and can vary in size from 300 to 1,200 soldiers.

“There might be eight battalions [of SNA in Sector 3] but the most in one battalion is probably 250 and the least is about 150,” said Fitwi, implying that SNA battalions are under-strength.

“There is the problem of SNA doing private security work [because of low pay] and they are asking us all the time for ammunition. The soldiers come from clans and almost all the army is newly recruited. There are no tactical skills, and there is no command and control,” with SNA soldiers coming and going from their bases as they please, he added.

AMISOM forces and the SNA have rolled back huge swathes of Al-Shabab-controlled areas, especially since the UN February 2012 endorsement of the new Concept of Operations (CONOPS), which saw AMISOM’s troop numbers increase from 12,000 to 17,731 uniformed personnel.

Some analysts term AMISOM’s capturing of territory as “mowing the lawn”, which suppresses the immediate threat, but fails to address the underlying causes of the conflict.

Changing tactics

Mohamed Mubarak, a Mogadishu-based security analyst and founder of the anti-corruption NGO Marqaati, told IRIN success against Al-Shabab for AMISOM was a double-edged sword, as “once Al-Shabab has been sufficiently neutralized, AMISOM risks becoming viewed as an occupying force. However, AMISOM would not want to leave until they have confidence in the capacity of the SNA.”

Fitwi said the nature of the conflict was also changing, as Al-Shabab no longer always confronts AMISOM and has adapted more to “guerrilla-type warfare” with the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and landmines.

“In the future [AMISOM] tactics need to change. It’s time to shift to the use of special forces, but AMISOM has no special forces, but we can use small units to lay ambushes against Al-Shabab,” he said.

© Guy Oliver/IRIN

Tesfaye Gurmay, a colonel in the Ethiopian army and AMISOM Sector 3 operational head, told IRIN the security situation in the sector was “not alarming” and the main security problem was “the deeply rooted conflict within the clan system, and not Al-Shabab”.

Mubarak in a February 2014 African Arguments briefing said: “Since the TNG days, the transitional governments of Somalia have given military honours to clan and warlord militia commanders simply to appease said groups [clans].

“This has resulted in an army of semi-literate officers at every level: from the veteran warlord Indha Adde promoted to general from nothing by Sheikh Sharif [Ahmed, the former Somali president between 2009 and 2012] in 2010, to former ICU [Islamic Courts Union] foot soldiers promoted to captains and majors from 2009.”

Mubarak told IRIN: “Because of clan politics and the realities of Somalia during the civil war, some clans have more representation in the armed forces and use the SNA cover to achieve their objectives.”

“In today’s Somali army, clan loyalties trump national identity; without this being rectified by rehabilitating and decommissioning clan militias, continuing to arm the Somali army is akin to fuelling clan wars,” Mubarak said in the briefing note.

Arms proliferation

The Somalia and Eritrea Monitoring Group in a February 2014 briefing – following the partial lifting of the country’s more than 20-year-old arms embargo in March 2013, which was eased so that Somalia could re-equip its security forces – pointed to the “high level and systematic abuses in weapons and ammunition management and distribution”.

The briefing said: “The Monitoring Group has identified at least two separate clan-based centres of gravity for weapons procurement within the FGS [Federal Government of Somalia] structures. These two interest groups appear to be prosecuting narrow clan agendas, at times working against the development of peace and security in Somalia through the distribution of weapons to parallel security forces and clan militias that are not part of the Somali security forces.

“Dealers now say the greatest supply of weapons is from SNA stocks”

“In addition, the Monitoring Group has obtained separate photographic evidence of a new AK-pattern assault rifle in one illicit market which matches the exact type supplied by Ethiopia to the SNA. The serial number on that rifle is in sequence with serial numbers inspected on Ethiopian-supplied rifles in Halane [Mogadishu’s main military camp],” the briefing said.

Information obtained by the monitoring group found poor controls on weapons and ammunition and their “sources in the markets indicate[d] that weapons are being moved to Galkacyo, a major trafficking hub in central Somalia, as well as being sold to Al-Shabab in Jubaland [part of southern Somalia where Kenyan forces are deployed].

“Sources in the markets also claim that prior to November 2013, most weapons sold were black market weapons, whereas dealers now say the greatest supply of weapons is from SNA stocks.”