Four-year-old Osman came to the Kismayo Stabilization Centre earlier this year. Suffering from Kwashiorkor, a nutritional…

Four-year-old Osman came to the Kismayo Stabilization Centre earlier this year. Suffering from Kwashiorkor, a nutritional disorder caused by lack of protein, he developed a flaky rash all over his body giving his skin a rusty look.

Osman’s family lives in a flood-prone area along Juba River that is known to suffer from a disruption in food security. But with help from the stabilization centre, he has responded positively to treatment and is expected to make a full recovery.

Osman is just one of 300,000 children in Somalia who are suffering from malnutrition, with close to 60,000 under the age of five years in critical condition and in need of urgent therapeutic feeding. The southern Somalia port city of Kismayo is home to the only feeding centre in the region, and is currently overwhelmed by the sheer number of children in need of its nutritional therapeutic feeding program.

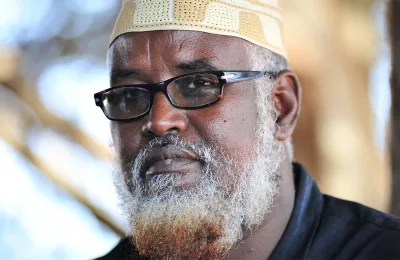

The Kismayo Stabilization Centre has seen an influx in cases of malnutrition, sometimes treating up to 150 children in its 90-bed capacity facility. In January and February alone, 386 children were admitted to the centre, forcing Bashir Mohamed, the centre’s general supervisor, to convert some of the offices into wards.

“We began by converting the isolation ward to a normal ward and now we had to make room in some offices to deal with the high admissions,” said Mohamed. “Also, children are accompanied by the parents or caregivers who will stay with them for the duration of the treatment.”

The ICRC begun supporting the Kismayo Stabilization Centre in 2014, and another in Baidoa, Bay region, which opened in May 2015. However three similar centers in the region closed down in recent years causing the increase in patients in the remaining centres.

Like Osman, Abdi Ibrahim was diagnosed with Kwashiorkor at the stabilization centre. But the two-year old is also suffering from anemia and a lack of appetite. He must be fed through a nasal tube.

What makes Abdi’s case worse is the fact that he is actually overweight due to oedema, a condition characterized by swelling of the body due to fluid retention. He arrived at the stabilization centre weighing 7 kilograms, which is one kilogram overweight, but the nurses expect his weight to come down soon.

Abdi is one of eight children who travelled 90 kilometers with his mother from Kanjaron district to receive treatment at the centre. The family leads a nomadic life and depends on livestock for sustenance. However, a recurring drought in Somalia’s Lower Juba region has forced the family to resort to a diet of maize and water to survive.

Two-year-old Timiro was severely malnourished and suffering from tuberculosis when she arrived at the Kismayo Stabilization Centre. She is at the centre with her 13-year-old sister because her mother is taking care of her seven siblings at one of the 42 displacement camps around Kismayo city.

Timiro is slowly recovering and gaining weight under the therapeutic feeding program and is expected to be discharged soon.

According to a 2016 humanitarian needs overview report, acute malnutrition rates in internally displaced settlements like Timiro’s are frequently above the emergency threshold of 15 percent.

This is why these stabilization centres are needed. When patients are discharged, their care givers are provided with nutritional advice and supplementary foods such as a peanut-based paste called Plumpy’nut to help their children stay healthy.

Families are provided with seeds and training on how to grow tomatoes, beans and carrots to sustain a healthy diet. The ICRC also provides 300 USD cash assistance to allow mothers to make up for the lost income for the treatment period. The transport cost to the centre is reimbursed and fare to return home is also provided.

Last year, these two centres treated over 3,000 cases of severely malnourished children. In a time of rising malnutrition, the centres remain critical to the care of the children.

Source: ICRC