[New York Times] — The day after his oldest son was convicted of conspiring to join…

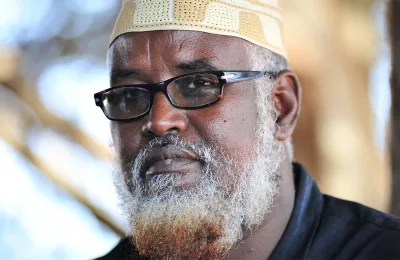

[New York Times] — The day after his oldest son was convicted of conspiring to join and kill for the Islamic State in Syria, Abdihamid Yusuf just wanted to go home and rest. But bills were stacking up, so on Saturday morning he and his wife visited the jail and then reopened Hooyo’s Kitchen, the small Somali restaurant where they serve plates of chicken, rice and bananas.

“We try to survive,” Mr. Yusuf said.

The trial of his son and two other young Somali-American men splintered families and opinions here in the country’s largest Somali community. Former friends testified against one another, describing how they had watched propaganda videos, bought fake passports and plotted their paths to Syria. Family members squabbled in the halls of the courthouse. Some said they had been threatened or shunned.

When the jury came back on Friday afternoon, Mr. Yusuf did not even get word in time to reach the courtroom to see his 22-year-old son, Mohamed Farah, and the two other defendants, Guled Omar, 21, and Abdirahman Daud, 22, declared guilty. A total of nine men — including another of Mr. Yusuf’s sons, Adnan — have been convicted in the case.

Federal prosecutors say the case shined a light on the persistent problem of terrorist recruiting here. Law enforcement authorities have said that more than 20 young men from Minnesota have left to join the Shabab militant group in Somalia and that more than 15 have tried or succeeded in leaving to join the Islamic State.

But it also opened wounds among families, and at the end of the trial, some in the community praised justice served, while others pointed to what they called another injustice.

Deqa Hussen said she had learned the price of cooperating: “They’ve been calling me snitch.”

Her oldest son, Abdirizak Warsame, 21, briefly acted as the leader of a group of friends as they planned to travel to Syria in 2014. He pleaded guilty and testified for prosecutors, telling the jury how he had wanted the rewards of martyrdom.

Now, Ms. Hussen said, longtime friends and strangers have accused her of selling her son to the government. During the trial, she said, the mother of another defendant threatened her life.

“I have to respect the government and I have to respect my son,” she said. “My culture is a culture of silence. You cannot speak your rights.”

Some in the Somali community praised the government. They said that the three defendants had gotten a fair trial, and that they hoped the convictions would prompt candid talks about extremism and its allure to some young men here.

“This is good for the community,” said Mohamed Ahmed, a gas station manager who created an online cartoon character, Average Mohamed, to condemn extremism. “It unmasks the fear, forces us to think deeply. We can either confront it or bury our heads.”

Jibril Afyare, an IBM software engineer and community activist, spoke of vigilance. He said he talked regularly to the United States attorney about the threat of recruitment by terrorist groups, and has a local police captain’s number on speed dial.

“We cannot afford even one Somali youth to be recruited by extremists,” he said. “It’s dangerous for the country, and it’s dangerous for the Somali community.”

But others called the case a setup, and said the defendants had been goaded to act and praise terrorism by a onetime friend who made secret audio recordings as a paid federal informant. In barber shops and cafes where the case flashed on television screens, young men and old said the trial would harden the community’s relationship with law enforcement, and said the defendants did not deserve potential sentences of life in prison.

“People think the trial was dishonest and was done in a hurry, that this is a conspiracy,” said Jamaal K. Farah, 35, a barber and comedian who goes by the name Happy Khalif and has attracted hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube.

Mr. Farah said he used to give haircuts to some of the nine friends who have now pleaded guilty or been convicted. He rejected portrayals of them as eager, would-be militants who spoke of wanting to spit on the United States, kill Turkish security forces or die as martyrs.

The case focused on conversations and events in 2014 and 2015. Prosecutors said some of the defendants had watched Islamic State propaganda videos, met to discuss routes and timing to leave for Syria, tried to buy fake passports from an undercover F.B.I. agent and played paintball to train for combat.

But to Mr. Farah and others skeptical of the convictions, the men were not defendants or terrorists, but boys, brothers, kids who had messed up but deserved a second chance.

“These kids used to be part of this community,” Mr. Farah said. “This country gave us hope and a better life. We think this trial was a total injustice.”

As he watched boys play basketball outside a community center in central Minneapolis, Burhan Mohumed thought of his friend Guled Omar.

He said Mr. Omar had played here before “he was caught up in that storm.” Mr. Mohumed attended the trial regularly but was barred from the courthouse after he intervened in a fight and argued with court security officers.

After the trial, Andrew M. Luger, the United States attorney for Minnesota, condemned the threats and courthouse scuffles as intolerable and “unheard-of.”

Mr. Mohumed supported the three defendants and, echoing others here, he was upset they could face life in prison even though they never left for Syria and never pulled a trigger.

“If they can convict them on words and thoughts, it’s over,” he said. “People will not feel safe in our communities.”

But prosecutors said the case involved far more than thoughts. They said the defendants were ready to kill for the Islamic State and had made well-documented efforts to fly out of Kennedy International Airport or cross the Mexican border to travel to Syria.

On Saturday, Mr. Yusuf said, his wife insisted that they go back to work after they visited their son in jail. He said he had taken time off from his job driving a school bus to deal with the criminal cases against his sons. But they still had five other children to care for.

So they opened Hooyo’s Kitchen, in a Somali shopping center stuffed with rug stores, barber shops, classrooms and kitchens, four floors above Mr. Farah’s barber shop.

As his wife cooked, Mr. Yusuf rushed food to customers. People stopped by to tell them to be strong. Mr. Yusuf’s thoughts tilted back to his sons.

He said Mohamed Farah, the oldest, was hopeful about sentencing, and had told him that whatever came next was God’s will. He worried about the cost of funding two commissary accounts so his sons could call him from jail. He worried about the distance he would have to drive to visit them.

“It’s not fair,” Mr. Yusuf said. But he said they were propped up by faith. “We believe God will give, no matter what.”