The recent meeting of Somalia’s regional leaders in Dhusamareb, the capital of Galmudug State, without the…

The recent meeting of Somalia’s regional leaders in Dhusamareb, the capital of Galmudug State, without the attendance of the federal government, indicates that there are political turmoil and disunity among the bureaucratic elites in Somalia.

The current political crisis between the regional states and the federal government, however, is about two main issues. The first concerns the country’s political system, particularly the devolution of power between the federal and regional authorities. This is one of the main topics that the two groups have clashed over for the last 10 years. How power should be distributed, what sort of authority state leaders should have and what the federal government should control are all topics of debate.

Although the provisional constitution of the federal government notes these powers, it has not been helpful, especially when political disputes emerge between the two governance bodies, as the document has been a topic of controversy. Each side quotes the constitution and makes its own interpretations, undermining the relationship between the political groups.

On the other hand, their underperforming relationship has also slowed down the progress that the government in power needs during its four-year term in order to overcome the agonizing political, economic and social challenges that the country has been facing since the central authority collapsed in 1991.

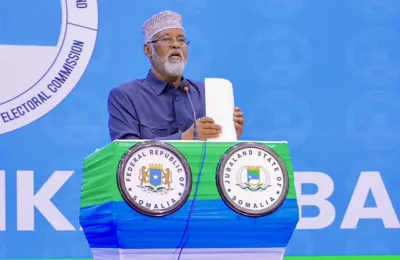

The second issue that has been a topic of political conflict is elections, both parliamentary and presidential. Since the national independent electoral commission of Somalia announced that one-man-one-vote elections cannot take place in the country and then proposed a term extension for the current government, regional state leaders objected to the plans and urged balloting to be organized on time. Furthermore, they called possible term extensions unlawful and illegitimate.

This is one of the reasons why regional state leaders justified their recent meeting in Dhusamareb. In addition, they were able to discuss other matters including security, development, regional cooperation and the general direction of the country. While it is constitutional for states to meet to discuss cooperation and collaboration among themselves, given the country’s political situations, their meeting demonstrates the existence of an internal crisis.

Since the end of the Sharif government in 2012, holding elections on time has been a topic of conflict, which needs to end, among Somali political elites.

Repeated crises

Of course, this is not the first time that the regional state and federal government leaders have been at odds with each other over the last four years. Not that long ago, Puntland State leaders opposed the Banaadir representation bill that mandated a 13-member increase of the upper house. After significant turmoil, the lower house approved the bill and the president called it a victory, but some regional leaders and opposition parties were suspicious and doubtful, believing the move was more political rather than meeting the expectations of the Banaadir region.

Of course, constant disagreement and differing viewpoints and beliefs is how politics is supposed to work. It is indeed something normal, and no one can complain about that, but what worries Somalis is the repeated internal political conflicts. It seems like there is nothing that regional states and the federal government can agree on. They are totally at odds, with each heading in a different direction. They are not even on the same page regarding general issues like the country’s political system, which is federalism, the devolution of power or natural resource distribution.

To be honest, this constant political turmoil and conflict over fundamental issues is holding the country back and leaves many Somalis feeling hopeless and desperate to take actions that could damage the nation’s security and the safety of its citizens. Of course, failing to find solutions to their political disagreements so the country can move forward means that the rate of unemployment will increase, economic opportunities will shrink, corruption will reach higher levels, government institutions both at the regional and national levels will be ineffective and the life’s work of two generations will be lost. In fact, if our current leaders continue on this path of not coming together to agree on something that can help us solve at least some of our major problems, then the wounds they leave will be passed on to the next generation, which they will then be forced to deal with them again.

Therefore, our leaders should wake up and understand how the modern world functions, forget their individual interests and focus on what is good for the country and good for the people they govern. They must look back at history and learn lessons from our past. They must notice what the last 30 years of fighting has brought us, and understand that the survival of two generations is in their hands and whatever decisions they make will shape our future – whether we prosper or suffer from poverty, famine, a lack of education, poor health services and a lack of rule of law and order. Therefore, governing, solving the problems of a country that is recovering from civil war and tackling challenging issues such as poverty, mistrust among the people and terrorism that creates insecurity, Somalia’s biggest problem, requires a lot of rationality, compromise, inclusivity and teamwork.

The way forward

There is no doubt that the repeated internal political crises between regional states and the federal government has impaired the country’s ambitions and development. That includes crafting a political structure that would allow the two bodies to work together without being at odds when decisive issues such as elections and other important matters come up. Therefore, ending this rift is the only way that our leaders both at regional and national levels can compensate for the time they wasted by creating this internal crisis rather than solving some of our major political and socioeconomic problems.

Our dysfunctional bureaucrats must also know that we, Somalis, are tired of being at war with each other and being on mainstream media all the time due to drought or famine. Our youth do not need to suffer from a lack of adequate education or joblessness. They are desperate for a country and environment that is better than the one in which they were born. They want to have a brighter future full of opportunities. Our adults no longer want to be without adequate health services, and they tired of traveling abroad just to receive basic medical treatment. It is clear and obvious to everyone that we are tired of the status quo and we are desperate for peace and functioning institutions that can deliver effective government services for us.

Having said that, to end the ongoing political crisis between the federal government and regional states, three major steps need to be taken. First, leaders from both groups must meet to discuss matters they differ on, including when elections will take place. Political realities on the ground demonstrate that term extensions without regional acceptance will cause more turmoil and destabilization. And of course, this does not serve the interests of the people or the country, as Somalia cannot afford another civil war that would only help terrorist groups who have been waging attacks against the civilians, government institutions and the international community for years. As political understanding among our bureaucrats is a prerequisite for the improvement of security in Somalia, so too will agreement among them will contribute to the eradication of groups like al-Shabaab and Daesh in the country.

Second, in their discussions, they must focus on ways forward and avoid blaming each other. They must keep in mind that the only way they can agree on something that is beneficial for the country and its people is if they solve their differences by showing compromise and mutual concession.

Third, this repeated political crisis that emerges at election time needs to end, and the only way this can be stopped is if our bureaucrats agree on some sort of political framework that will help our country avoid further rifts and crises.

BY MOHAMED SALAH AHMED

*Ph.D. candidate of political science and public administration at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University