QARDHO, SOMALIA — You can find Fatuma Warsama on the side of the road somewhere between Qardho…

QARDHO, SOMALIA — You can find Fatuma Warsama on the side of the road somewhere between Qardho and Bandar Bayla in Somalia’s semi-autonomous Puntland region. The 50-year-old pastoralist and her family traveled for miles across this dry, cracked earth in search of pasture for their goats.

“We heard of some signs of rain in this area, so we came here…but the situation is just the same. There is nothing,” Warsama said, pulling the end of her bright orange garment over her head to block the blazing midday sun. She sits outside the makeshift hut that has become her family’s new home.

“We can’t get milk or meat now…we are eating white rice,” she says.

Pastoralists like Warsama depend on their animals to survive. But after three consecutive seasons of poor rainfall in the region, severe drought is decimating their herds. Somalia has already lost nearly a third of its livestock, says the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The remaining animals grow weaker each day. Humanitarian organizations are now racing to prevent a repeat of the 2011 famine that killed over 260,000 people in the Horn of Africa nation.

“The pastoralists depend on livestock for daily cash, so with the drought you can imagine the income is very low. The prices of animals drop down and the price of food increases. So it impacts directly and indirectly on the livelihood of the households,” says Khalid Saeed, the head of FAO’s livestock sector in Somalia.

Livestock contributes to about 40% of Somalia’s Gross Domestic product. In 2014, the country exported a record 5.3 million animals to mostly Middle Eastern countries, the highest such figure in two decades, according to FAO.

But with drought come fears of disease which prompted Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations to place a ban on Somali meat imports in December 2016, effectively paralyzing the market.

“Before the drought, the animals were good and we used to sell them. The biggest animal would fetch $100. The lowest we used to get was $50,” Warsama said.

Now, that figure is closer to $30 per animal.

The deteriorating situation means 6.2 million Somalis face acute food insecurity, and more than 2.9 million are at risk of famine, says the UN.

In Puntland, Somali veterinarians working with the FAO are canvasing an area so vast that you can go days without seeing human activity. The initial push aims to see 2,250 animals a day for 30 days – giving them immunizations, vitamin boosters and treatment for things like parasites, respiratory diseases and injuries. A second round starting in April aims to bring the total number of animals treated up to 20.5 million, impacting as many as three million families.

It seems like a massive undertaking, but the FAO says the cost per animal treated is only $.40. The project reports directly to Somalia’s Ministry of Livestock.

“The Somali people depend on the animals. If there are no animals, there is no life in Somalia,” said Jamila Mohamed Ali, a 20-year-old veterinarian working with the FAO in the Puntland region.

The FAO is also sending delivery trucks through the region to deposit cool, clean water into hand-dug pools. They are supposed to deliver separate water for the animals and humans, FAO says, but the dire circumstances mean pastoralists are sharing the water with their livestock, risking disease and infection.

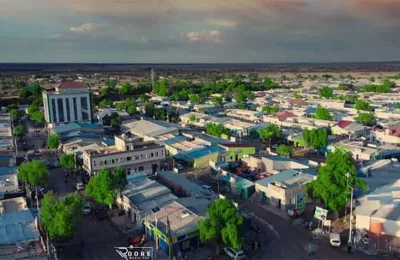

Some pastoralists have lost so many animals that they are migrating to informal camps near urban areas in search of food and water. More than 187,000 people were displaced during a three week period in March alone, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reports. In all, the drought has displaced nearly half a million people in Somalia.

Hawa Mahmoud has been living with her husband and three children outside the town of Qardho since November in a shelter made from sticks and mud.

“We left half of our possessions behind. We didn’t have a car to transport us so we made three trips by camel,” Mahmoud said.

Mahmoud’s fourth child is due any day now, but there is no hospital in this camp or in others around the country. That is already having worrying consequences. Nearly 16,000 people have contracted cholera in Somalia this year, and the disease has killed more than 365 people, the U.N. reports.

Towns are struggling to meet the needs of thousands of hungry new arrivals. Decades of conflict and chaos have left the Somali government with few resources and limited reach.

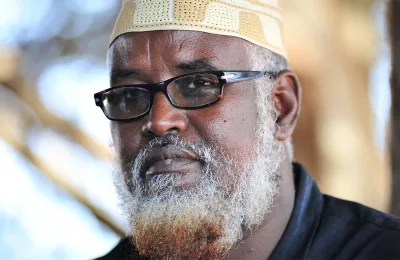

“There are a lot of problems here. [The displaced] don’t have any livelihoods. They’ve become a burden to the town,” said the mayor of Quardo, Abdi Said Osman.

Business owners in Quardo have been been extending credit to people living in the nearby camps, but no one knows how long that generosity can last. Mahmoud’s husband, Abdinoor Abdillah Hassan, has been able to scrape together some income with odd jobs.

“I do manual labor. I use my strength to make money. We have nothing else,” he said.

Neha Wadekar

VOA