Recent executions in Somalia put the quality of justice delivered by military courts into question. Somalia’s…

Recent executions in Somalia put the quality of justice delivered by military courts into question.

![Three men found guilty by a Somali military court of killing civilians and masterminding a recent attack on the Presidential Palace were tied to poles shortly before they were executed by a firing squad in capital Mogadishu August 3, 2014 [Reuters]](https://horseedmedia.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/20148241050727580_20.jpg)

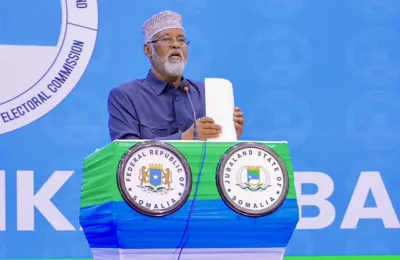

Such rapid executions once again call into question the quality of justice in Somalia’s military courts. The government should try civilians before civilian courts, respect the presumption of innocence, ensure that confessions are not extracted under duress, and allow defendants adequate time for appeals. Sadly, Somalia’s new military court chairman, Col Abdirahman Mohamed Turyare, has boasted of flagrant violations of these requirements under international law. He recently told the media that his court was waging a “new war against terrorists.” Under international law, the death penalty is permitted only after a rigorous judicial process – a fair trial in which the defendant has adequate time to prepare a defence and appeal the sentence, among other requirements.

In March, Human Rights Watch (HRW) released a report detailing how Somalia’s military court proceedings “fall short of international fair trial standards”. Relatives of defendants and independent observers have very limited access to the hearings, allowing the court to operate without oversight. A central concern was the speed at which death sentences have been carried out. HRW opposes the death penalty in all circumstances as an inherently cruel and irreversible punishment. That concern is even greater given the due process concerns we identified with the military court.

Unfortunately, these practises appear to have been getting worse in recent months.

Thirteen executions have taken place in Mogadishu in 2014, nine been carried out just since July. Eleven of those executed were not members of the Somali armed forces; the majority accused of being Al-Shabaab members or fighters. A man accused of carrying out an attack on Maka al-Mukarama hotel in Mogadishu in November 2013 was sentenced and executed within just over two weeks in July.

Carrying out death sentences so rapidly prevents defendants from filing an appeal. It also makes it less likely that the president will be able to review the case for a possible pardon or commutation.

The military court has tried defendants for a broad range of crimes not within its jurisdiction, notably common crimes against civilians.

Turyare told the media that parents of Al-Shabaab suspects will be arrested and he claimed some were already in detention. “It is failure to exercise responsibility of parent-ship. It is your responsibility as father or mother to report to the police that your children are missing or went to terrorist group,” he said. Arresting families of suspects is a form of collective punishment that is contrary to fundamental principles of justice.

In its recent decisions, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has called on countries to prohibit trials of civilians before military courts and to restrict the cases appearing before these courts to military offences committed by military personnel. Somalia should comply with these decisions by transferring civilian cases to civilian courts, rather than cementing an abusive practise.

Even the outdated Somali military law doesn’t grant the court such powers. Turyare claimed that trying Al-Shabaab suspects under the military penal code is justified, but HRW’s assessment of the code found the legal basis for the trial of civilians in the military court, including Al-Shabaab members not taking part in hostilities, to be doubtful.

Defendants are also often held in facilities run by Somalia’s national intelligence agency, notorious for mistreatment during interrogations. Turyare told the media that those recently executed had “confessed”. International human rights law and Somalia’s provisional constitution state that no one can be compelled to testify against themselves or to confess guilt. This basic standard helps to protect defendants from being coerced or tortured into confessing.

The state-run Somali National Television has contributed to undermining the defendants’ chances of a fair trial by broadcasting interviews with them during their detention and trial, describing their alleged involvement in attacks. This shows governmental disregard for the presumption of innocence.

Amid these swift executions, Somalia has called on Kenya to extradite to Mogadishu an alleged Al-Shabaab journalist who is reportedly under arrest in Kenya. While Kenya still has the death penalty on its books, it has not executed anyone in decades, and should not return anyone to Somalia who surely will not receive a fair trial.

The Somali government should reform its courts before making requests for extradition. The president should impose a moratorium on the death penalty, and his government should work to ensure that all national courts, civilian and military, respect fair trial standards. Without serious improvements in the quality of trials, the injustices of the past will continue.

As one Somali defence lawyer told me: “I believe that all human beings, including Al-Shabaab suspects, have the right to fair trial.” Wise words that the head of the military court and the Somali authorities should hear if they hope to rebuild people’s trust in their justice system.

Laetitia Bader is an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.

Source: Aljazeera