Kenya marked the fourth anniversary of al Shabaab attack on the El Adde KDF base in…

Kenya marked the fourth anniversary of al Shabaab attack on the El Adde KDF base in Somalia’s Gedo region last week.

The January 15, 2016 attack left scores of soldiers dead.

The death toll was not made public but it was in excess of 147 students killed in the militants’ attack on Garissa University on April 3, 2015.

As the country came to terms with the massacre, the government promised thorough investigations and a “painful lesson” to the militants.

Fresh details have, however, emerged indicating that the KDF command at the base likely ordered the camp to be blown up to avoid the soldiers being taken prisoner.

In The Soldiers Legacy, Lance Corporal Erick Lang’at, a survivor of the attack paints a grim picture of what happened.

Lang’at had just taken over sentry duties after a briefing by the outgoing sentry team.

The D Company and 9 KR had been deployed to the base 15 days before the attack.

On January 14, the outgoing sentry team had observed the movement of a vehicle a distance from El Adde town. The team suspected it was on routine smuggling activity.

“At around 5.15am on January 15, a vehicle’s headlights briefly flashed in the base’s direction and then turned off. Within no time, the engine ignited and the vehicle hurtled towards the operation base,” Lang’at writes.

He recalls the unsuccessful efforts to stop the fast-moving vehicle with rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) fire.

The driver avoided the trenches before hitting a tree in the middle of the base and detonating the bomb.

“After the explosion, everything went silent for about three minutes. In its wake, the blast had destroyed part of the operation base, leaving only one survivor in the immediate environs of the epicentre,” he writes.

Although Lang’at lacks words to describe the intensity of what turned out to a massive Vehicle Borne Improvised Device – VBIED, he says, “It is the kind of thing that I had only seen in movies. It changed from pitch black to a ball of fire that illuminated and blinded people within a radius of 200 metres and probably more”.

He continues: “As if that was not enough, there were two follow-on blasts. When I came back to my senses, much of the operation base was in disarray. I saw a thick cloud of smoke and it was clear to me that several bunkers had collapsed. At that time I was bleeding in the right eyebrow.”

His first instinct was to continue firing but a lot of damage had already been inflicted, thus reducing friendly firepower at the operation base. The enemy had already stormed the base and embarked on a series of attacks.

A few minutes later, the writer says Captain Mbau Gichui, the company’s second-in-command, assembled them to repulse the attackers.

In the other sector of the operation base, Sergeant Abudullahi Issa and Philip Kipyegon directed the troops on how to respond.

According to Lang’at, many militants were killed, but they kept attacking in waves.

“I realised I had run out of ammunition and took a magazine from a colleague who had succumbed. Recognising that holding onto the defended locality was no longer tenable, the troops abandoned their positions in small groups to make it difficult for the enemy to pursue them,” Lang’at recalls.

He and his team withdrew through the route breached by the VBIED.

However, when they were almost at the first razor wire obstacle, a colleague he was following closely was shot from behind.

“Due to the criticality of the injury, the wounded soldier turned his rifle and shot himself on the lower chin to avoid being captured by the enemy. He died instantly,” the book says.

The writer continued moving towards the operation’s base outer barrier. Unfortunately, another sergeant who attempted to use the same route got entangled in the razor wire and died from the injuries.

On his way out, Lang’at linked up with some other survivors and began their march to safety.

The soldiers discussed the safest route to follow and upon agreement, they agreed to split, with some walking along the road to link up with the rescue teams while the others, Lang’at included, moving across.

MISSING SOLDIERS

“Unfortunately, the seven who used the road are still missing in action to date,” he says.

Lang’at’s group traversed the scrubland and after 30km, one of them suggested they take a brief rest. “We agreed though hesitantly and it is at this point that one of us passed on while sitting under a tree. We said a prayer for him and reluctantly left his body behind.”

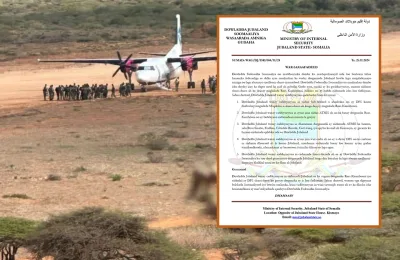

Amid the confusion, Lang’at remembered he had a phone which he used to reach his commanding officer, who luckily linked him with the search pilot.

“Luckily, communication went through and the rescue helicopters located us. I cried in relief when we landed in a Kenyan military camp along the common border with Somalia.”

Al Shabaab claimed to have captured 12 Kenyan soldiers, including the commanding officer.

These soldiers, according to Chief of Defence Forces (CDF) General Samson Mwathethe, are being used by the militants as a human shield.

Although the KDF rubbished reports that the country had lost over 180 soldiers, a new death toll from open-source information indicates that the deaths ranged from 141 to 185 troops.

Around 40 survivors managed to escape and an unknown number are still unaccounted for.

Sources said DNA samples were taken from 143 bodies at the scene, most of which were burned beyond recognition.

Under the Amisom peace-keeping mission, Kenya has 3,000-plus troops manning Sector 2.

The troops have contributed to Amisom’s rollback of territory controlled by Shabaab.

Global terrorism database compiled by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Response to Terrorism (better known as Start indicates between 2013 and 2017, Kenya has suffered 373 terror attacks. Some 929 people have been killed, 1,149 injured and 666 taken hostage.

President Uhuru Kenyatta has maintained that KDF soldiers will remain in Somalia until the militants are wiped out.

Source:the-star