A continent filled with poverty and corruption is a tricky place to do business, but the…

A continent filled with poverty and corruption is a tricky place to do business, but the US and its democratic allies need to engage.

Many years ago, on a BBC assignment reporting the Angolan civil war, I was billeted in a warehouse with some of Jonas Savimbi’s Unita guerrillas. In faraway places I liked to carry books that had nothing to do with my assignments. That night, as I ate a Michelin zero-starred supper, I read a history of the English Civil War, its cover painting showing Oliver Cromwell clad in an armored breastplate.

An officer from Zambia, which was supporting Unita’s rebellion, leaned across and gazed curiously at the image. “What is this,” he asked, “is it a robot?” A stab ran through me, not of laughter but of wonder. That soldier’s question reflected not stupidity, but instead the cultural chasm between Africa and the West, which has fascinated me ever since.

I have travelled widely in what British Victorians used to call the Dark Continent, but which I think of as the brilliantly lit one, because I have had so many extraordinary experiences there. Africa teems with natural beauty and manmade horrors, riches, talent and some of the worst governance on the planet.

Today, while the US and allied democracies obsess on the crises of Europe, Asia and the Middle East, Africa’s 1.4 billion people are beset by Russian and Chinese disinformation campaigns that enjoy considerable success, firehoses of propaganda against the West.

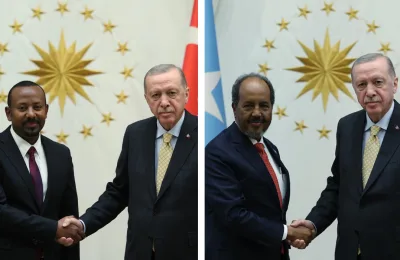

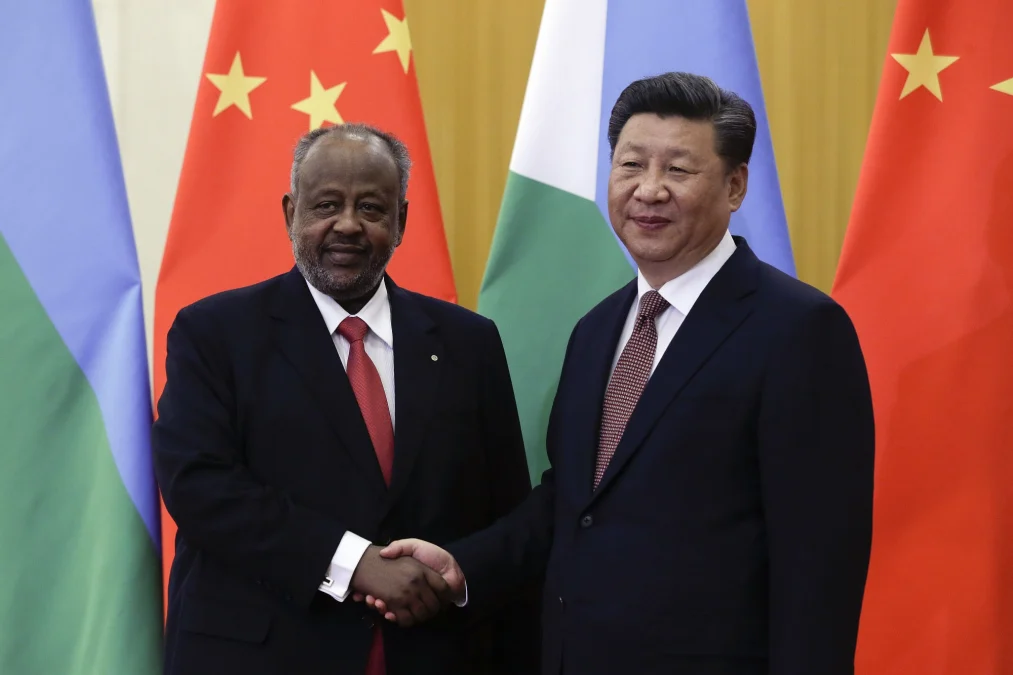

Many African nations abstained in the United Nations vote condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They are forging ethics-free economic partnerships with such countries as India, Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. Chinese companies have become market leaders in African digital infrastructure, mostly because their Western competitors decided early in this century, badly mistakenly, that the local people were too poor to afford cellphones.

Russia has dramatically expanded its footprint, signing military deals with at least 19 African countries since 2014 and becoming top arms supplier to the continent. In November 2019, President Vladimir Putin hosted the first Russia-Africa summit in Sochi, securing trade, energy and military deals.

As with Russia’s backing of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, in Africa the Kremlin sees opportunities to expand its sphere of influence by exploiting conflict, manipulating governments and selling arms to earn deals for its state-run energy companies. Russia not infrequently backs several factions in African civil wars, fomenting instability. Russia’s mercenaries, notably the Wagner Group, blur the line between private and state interventions in Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Madagascar and Mozambique.

Western governments seem indifferent. The last American president to visit the continent was Barack Obama, in 2015. US trade with Africa has fallen steeply, from $142 billion in 2008 to $64 billion in 2021, and now accounts for barely 1% of America’s global commerce.

During the worst of the Covid pandemic, pleas for drugs went largely unheeded by the rich world — only around one in five Africans is fully vaccinated. The droughts ravaging East Africa, manifestations of climate change, command little notice. Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia are experiencing economic turmoil caused by Covid and the disruption in global food and energy markets resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

All this alongside rising unemployment and inflation. Some countries, despairing of creating jobs for their people at home, have institutionalized “labor externalization” programs to dispatch teenagers abroad, especially to provide domestic services in the Arab world.

In Kampala, Uganda, a training center teaches young Ugandans to make beds, wash cars, use a microwave — 87,000 of the nation’s people went to the Middle East to work last year, and about the same number of Kenyans. The Global Fund to End Modern Slavery claims that almost all find themselves abused by their employers, sexually or otherwise — but the rock-bottom pay is better than anything they can get at home.

Many North African governments are increasing indirect taxes and cutting public services, hitting the poor hardest. These factors, combined with political repression, threaten the region’s stability. It seems ironic that while many Americans and Europeans are fiercely exercised about the historic evil of slavery, they take less notice of stuff that is happening today, also imposing miseries upon millions.

China, of course, sustains a huge commitment, its trade with Africa reaching a historic high of $254 billion in 2021. Up to 2 million Chinese, military and civilian, live in the continent. Beijing continues to pursue dominance of natural resources, while the West still focuses on humanitarian aid to disaster hotspots.

This seems a mistake. What happens in Africa, for good or ill, cannot fail to have an impact upon all our lives. If, as scientists expect, climate change increases privation, violence, hunger and unemployment in the Southern Hemisphere, migration to the north will become a tidal wave. If China is left almost unopposed to secure mineral riches and bases, Western industry must suffer and regional orientation toward Asia tilt more sharply.

I am of the generation that learned a lot of African history, most of it about Western and Arab exploitation. In 1800, there were 2 million slaves in Brazil, 900,000 in the US, and 800,000 in Spanish America; almost all were of African origins. During the 1860s, between 60,000 and 100,000 slaves passed through Zanzibar en route to Arabia. And in the ensuing decades up to 30,000 Abyssinians — modern Ethiopians — were shipped to the Middle East by Arab slavers.

One morning in 1830, readers of France’s Le Figaro were invited to applaud their army’s seizure of a great swathe of northern Africa. “The standard of France and of civilization flies over the walls of Algiers and over the wreckage of ancient Barbary,” proclaimed the paper. “Algeria is ours, women, eunuchs, dey and people. It was wonderful in the seraglio to see the plump odalisques lying in the arms of voltigeurs” — French sharpshooters.

The British, of course, behaved no better, convincing themselves that their stupendous land grabs on the continent reflected a humanitarian imperative. When the famous medical missionary and explorer Dr. David Livingstone died in 1873, the Times asserted that wherever he had gone in Africa “he had made the English name not only respected but beloved.”

Yet last month, a BBC correspondent reported that South Africa reacted in a conspicuously muted fashion to the death of Queen Elizabeth II, that country’s former head of state: “While some here are quietly mourning her and remembering, in particular, her unique friendship with Nelson Mandela, many others have chosen to focus, if at all, on the bitterly contested and enduring legacy of Britain’s empire.”

The article quoted Sibulele Steerman, a university student, standing beside an open sewer in an impoverished township outside Cape Town: “I wouldn’t say I don’t like the Queen — no, no, no. But my everyday reality is [affected] by the impact of colonization.”

A critical consequence of those empires is the irrationality of modern African national borders, reflecting old European rivalries rather than indigenous tribal or racial loyalties. True, absent Western 19th-century invasions, local leaders would have sustained their own wars and tyrannies. But Europeans must bear historic responsibility for decolonization struggles, some of which I witnessed myself, whose bloodshed disfigured the last half of the 20th century.

Today, these have given way to a new kind of violence, equally lethal. Jason Stearns, a specialist on African conflicts at New York University, has written that most African conflicts are being waged by factions that do not want to win control of nations, but merely to shoot their way to a share of wealth.

For many of those who participate, conflict has become a career, a way of life, in which ideology plays little part. In the past decade, the number of identified armed groups in Congo has doubled, to 120. There are an estimated 40 in South Sudan, 20 in Libya and dozens in Nigeria. Stearns writes: “Africa has entered an age of grinding low-level conflict and instability.”

Large areas of Mali, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan are now controlled by militarized factions. Partly as a consequence, the World Bank estimates that sub-Saharan Africa is home to more than half the world’s extreme poor, 433 million people in 2021.

Nigeria, one of the richest and most important nations in the continent, as well as the most populous, is struggling against Islamists in its northeast, banditry in its northwest and almost unbridled criminality everywhere. In 2021, it is estimated, up to 10,000 Nigerians died in armed clashes.

Twenty of the world’s 38 countries worst affected by conflict are in Africa, and five military coups have taken place in the past two years. These phenomena feed hunger, economic stagnation and migration.

Whenever I pass through Nairobi, it is common to glimpse black SUVs with tinted windows that belong to the warlords controlling South Sudan, who find the Kenyan capital a congenial base from which to direct their banditry. South Sudan should never have been legitimized as an independent state in 2011, because it possesses absolutely none of the machinery of government, justice and administration to make such status credible internationally or endurable for its people.

As Stearns puts it: “Insecurity has become a racket.” Well-meaning Western aid donors who support national armed forces are often backing oppression — in 2019, the US provided Uganda with $118 million in military aid, even though the country’s government routinely uses its soldiers to repress its own citizens. The French government deployed troops to Chad in support of a brutally authoritarian president, seeking his aid in stemming the cross-Mediterranean migration that is a huge problem for France and all Europe.

The economist Paul Collier, in his seminal books on African democracy or lack of it, argues the importance of fighting institutionalized corruption, both by obliging Western corporations to cease paying bribes and by ending the banking secrecy that facilitates embezzlement.

Partly because Western business is indeed cleaning up its act, China has become partner of choice for some of the most resource-rich nations in Africa, because of Beijing’s indifference to criminality, incompetence and brutality.

Many Africans vent bitterness about what they perceive as Western condescension. In a famous essay titled “How to Write About Africa,” Kenyan author Binyavanga Wainaina catalogued phrases that White authors turn into clichés: “After celebrity activists and aid workers, conservationists are Africa’s most important people … You need them to invite you to their 30,000-acre game ranch or ‘conservation area.’ ”

“When writing about the plight of flora and fauna, make sure you mention that Africa is overpopulated,” he continued. “You’ll also need a nightclub called Tropicana, where mercenaries, evil nouveau riche Africans and prostitutes and guerrillas and expats hang out. Always end your book with Nelson Mandela saying something about rainbows or renaissances. Because you care.”

In my days as a correspondent in Africa, I sometimes adopted such cliches, because of realities that I saw all around me. It was then, as it remains today, tough to do honest business. In the words of an aid-expert friend, “in Africa, if you secure a position of power and fail to use it to assist your own family and tribe, you are seen as not merely stupid, but wicked.”

A year or two ago I had a conversation with one of Britain’s biggest bankers, newly returned from Johannesburg. He had no plans, he told me, to invest in South Africa, despite its enormous resources and potential: “There are so many other places in the world with less financial and moral hazard.”

Perhaps the best case for putting money into Africa today is a compassionate one: to assist in saving the continent from implosion. But a relatively limited proportion of Western investors are that selfless and enlightened.

Some big players in Washington are conscious of American neglect, and seek to do something about it. At the 2022 G-7 Summit, the US launched its Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment, explicitly designed to counter China’s Belt & Road Initiative. Yet the US is still a relatively modest aid donor: It spends as a proportion of GDP just one-third of what France, Germany and the UK give, and a quarter of what Norway and Sweden spend. Moreover, some influential Africans scorn the new “Partnership,” as at odds with other American policies that discriminate against their nations.

The US Congress’s Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act seeks to hold accountable “governments and their officials who are complicit in aiding [Moscow’s] malign influence and activities.” It is condemned by such commentators as Zainab Usman, daughter of a former Nigerian president, for singling out Africa while ignoring Russian economic partnerships in India and the Gulf.

She writes: “The United States is seeking to resuscitate declining trade and investment relations with African countries while punishing these same countries for exercising their sovereign right to interact with another country, albeit a problematic one.”

Usman denounces US policy as “paternalistic.” She urges that the West should go beyond humanitarian disaster and famine relief, and pursue strategic investment in a region which offers enormous new markets: “What happens in African countries will increasingly shape the rest of the world.”

That’s undeniable. Africa has the youngest and fastest-growing population of any continent, with a median age of 19; 11 million teenagers join the labor market each year.

Yet Usman’s impassioned plea fails to address an obvious trap. Is the West, and above all the US, to compete with the autocracies by adopting a matching policy of indifference to human rights and kleptocracy?

I received a letter last week from a White South African who had been reading a memoir of mine, in which I wrote of the horrors I witnessed in his country during the era of White minority rule, and when reporting the 1965-80 White people’s struggle to retain control of Zimbabwe, then called Rhodesia. In view of the continent-wide bloodshed that has followed colonialism, he wrote to me, would I not concede that White rule had provided security and stability for many millions of Africans, Black as well as White?

I responded, of course, that whatever horrors disfigure large areas of Africa, the continent is now in the hands of its rightful owners. White people have always been intruders, often oppressors.

Today’s news is not all bad. There is excitement about the prospect that Africa could become a vast source of renewable energy — hydrogen empowered by solar and wind-generated electricity. Namibia and Morocco are in the forefront of speculation about this possibility.

Polls show that hundreds of millions of Africans retain a passionate desire for democracy, for a right to choose their rulers by vote, even or especially when they do not have it.

It would be absurd to deny the difficulty, for both Western governments and businesses, of trafficking with nations that are institutionally corrupt and lack effective administrative machinery. But vigorous attempts must surely be made, for reasons both of compassion and self-interest. Continued Western indifference will exact a historic price, not only from Africans but from the planet.

By: Max Hastings

A former editor in chief of the Daily Telegraph and the London Evening Standard, he is author, most recently, of “Operation Pedestal: The Fleet That Battled to Malta, 1942.”