Militant group Al-Shabab has lived up to its promise to step up attacks in Somalia, mainly…

© UN Photo/Tobin Jones

Militant group Al-Shabab has lived up to its promise to step up attacks in Somalia, mainly against government installations and personnel, during the holy month of Ramadan, which began on 29 June. Over 30 people have been killed in Mogadishu alone.

On 8 July, the presidential compound was attacked during the iftar evening meal. Assailants entered the gate using a car bomb, and then engaged in a two-hour gun battle with palace guards, killing 14 soldiers.

On 5 July, at least four people, including two children, were killed when a suicide car bomb was detonated outside of the parliament building. Just two days earlier a long-time member of parliament (MP), Mohamed Mohamud, was killed with his bodyguard when armed assailants opened fire on his car.

In response, the Somali government fired the police commissioner and head of the intelligence agency. Abdihakim Dahir Said, the police commissioner, was replaced by Mohamed Sheikh Ismail, while Bashir Mohamed Jama, the head of national intelligence, was replaced by Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan, on 8 July. Since then however, attacks have continued daily. Local media reported that the Ministry of Defence was attacked last night.

The presidential palace had previously been attacked in February, and the parliament in May. Following the May attacks on parliament, National Security Minister Abdikarim Hussein Guled resigned. On 8 July he was replaced by Ahmed Khalif Ereg.

Government inability to contain the violence has left many residents, especially in Mogadishu, in a state of constant fear.

“If you go looking for bread for your children, you don’t know whether or not you will come back safely,” a Mogadishu resident, who gave only his first name, Abdinasir, told IRIN. “I don’t have any hopes of it getting any better in the foreseeable future.”

“To reduce risk, I am staying indoors at night,” Laila Abdi, another Mogadishu resident, told IRIN.

Government accused of being weak, corrupt

The upsurge in terror attacks comes amid growing frustration with the state of politics in Somalia. Critics accuse the government of being weak, corrupt and inefficient.

In early May, over 100 MPs called on the president to resign. They cited 14 points of discontent, which included accusations of incompetence, failure to improve the security situation, failure to implement the constitution, and failure to revive the economy.

“The president is a spectacular failure. He did not keep a word of what he had promised prior to his election,” said Abdirahman Hosh Jibril, an MP and former minister of constitutional affairs, who was one of the people who signed the petition calling for President Hassan Sheikh’s Mohamud’s resignation.

“The preparation of the constitutional development process is way behind schedule, the boundaries commission has not been formed. On the security front, the president had his own six-pillar policy, but look now, the parliamentarians have been endangered and the presidential palace was attacked,” he told IRIN back in June, during the first set of attacks on major government posts.

Since March, when African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) troops and the Somali National Army launched a renewed offensive to capture towns in south-central Somalia controlled by Al-Shabab, the militant organization has fought back, targeting government and international organizations.

They have successfully attacked all three branches of government, the judiciary, executive and the legislative, and have launched regular attacks in Mogadishu. The armed forces, weakened by clan rivalries, equipment shortages, corruption and indiscipline, appear powerless to keep people safe.

“The Somali government does not have a regular army. The force’s loyalty is questionable. They are more accountable to their clans than the federal government of Somalia,” Abdisakur Sheikh Hassan, a lecturer and political analyst, told IRIN. “We need a national army whose main concern is defending the nation at all cost and bringing back security and stability.”

“To make matters worse, elements of Al Shabab have also infiltrated the security apparatus,” he added.

Somali police spokesman Qasim Ahmed Roble, however, rejected claims of corruption and dubious alliances on the part of the security forces. “We are working 24/7 to protect the people of Somalia. The accusation that we are mixed up with politics is not true. Security is not a political institution,” he told IRIN.

But in towns where Al-Shabab has retreated, it still controls access routes, and has been blocking off supplies. Combined with poor rains and a disruption to the planting schedule due to hostilities, the UN and many international organizations are now warning of the possibility of a new famine in the coming months.

One third of the population is in need of aid, and NGOs have been warning that communities are just “one shock away from disaster.” On 13 July, Turkish relief organizations, who represented some of the only international charities that still worked in Somalia, suspended their work in Mogadishu, according to local media.

“The elements that could tip Somalia into an acute crisis now stand before us – drought, continued conflict, restricted flow of commercial goods, increasing malnutrition and surging food prices,” noted the UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Somalia, Philippe Lazzarini, in a press statement on July 8.

Broader governance problems

Some see the shuffle in security positions as an important step forward, particularly the appointment of the experienced Ahmed Khalif Ereg as minister for national security, though the president’s decisions will probably continue to trouble him.

“Many of the policy decisions the president made early on have caught up with him. For example, he appointed only 10 ministers whereas the smallest [previous] cabinets were 18 or 25. This made a lot of politicians unhappy,” Abdirashid Hashi, deputy director of Mogadishu-based think tank Heritage Institute of Policy Studies told IRIN.

Meddling in the creation of due-to-be-formed federal member states, as the government attempts to implement a federal system, has also led to a lot of animosity.

“The process to form federal member states has been disorganized and inorganic. All state formation conferences thus far and negotiations to resolve subsequent disputes have been non-inclusive in some way – making the battlefield the preferred venue,” Tres Thomas an East Africa analyst and PhD candidate at George Mason University, told IRIN. Under the constitution that creates a devolved governance system, federal member states form the sub-national units of government.

“For example, in the Juba region, pro-Somali government ASWJ [militia group], and Interim Juba Administration forces recently clashed in the Gedo region [part of the proposed Jubaland] because the Addis Ababa agreement – reached after the controversial Jubaland conference – was an incomplete and non-inclusive political settlement.”

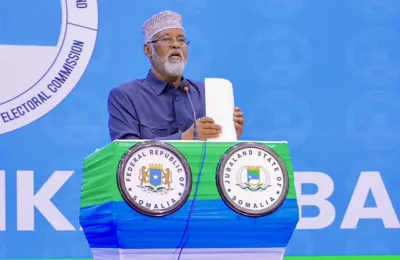

The Addis Ababa agreement creates a federal state of Jubaland, which will incorporate the territories of Gedo, Middle Juba and Lower Juba. But this agreement has run in parallel with other state building initiatives in the same region, and the process has been marred by confusion, mistrust and sporadic clashes.

“Anger will build among many players until the Somali government is seen as genuinely trying to do some consensus-building on a fair federalism process that benefits all stakeholders and reconciles decades-long grievances,” Thomas added.

“The political mood in Mogadishu is gloomy and citizens are not happy about the disorientation and lack of focus among politicians,” said Hashi.

“The whole government system is confused. Taking one guy out and bringing another in won’t change much,” Abdifitah Gelle, a Mogadishu resident, told IRIN. “There is a need for a complete reboot of the system.”