Human rights groups are warning that Kenya’s controversial Security Amendment Act still poses a threat to…

Human rights groups are warning that Kenya’s controversial Security Amendment Act still poses a threat to refugees’ rights despite a high courtdecision on Friday that suspends parts of the bill for 30 days pending a full court hearing.

The suspension included a section of the wide-ranging bill, popularly known as the ‘anti-terror’ law, that amended Kenya’s Refugees Act. The amendment stipulates that, “the number of refugees and asylum seekers permitted to stay in Kenya shall not exceed 150,000.”

Currently there are over 600,000 refugees, asylum seekers and stateless people living in Kenya, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

Although the cap of 150,000 can be reset by the National Assembly, rights groups fear that the new amendment will result in large numbers of refugees being forcibly returned. This would amount to refoulement, a serious contravention of international refugee law.

On Friday, the Judge ruled that other sections of the new act that deal with refugees will remain in place including a requirement that anyone who has applied for refugee status remain in designated refugee camps “until the processing of their status is concluded.” There are over 50,000 non-camp based refugees living in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, according to UNHCR.

A Court of Appeals will, within 30 days, rule on the constitutionality of 22 sections of the bill, which are being challenged by the Kenya National Human Rights Commission (KNHRC) and the opposition Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD).

The Security Amendment Act was passed on 18 December after a heated debate in parliament that culminated in a fistfight among members of the lower house. It was signed into law by the President the following day.

It took less than two weeks to draft and pass the law following a spate of terror attacks conducted by Somali terrorist group, Al-Shabab in Kenya. On 2 December, 36 people were gunned down by al-Shabab in a quarry close to Mandera town, an area close to the Kenya-Somalia border. Ten days earlier, less than 50 kilometers away, 28 bus passengers had been shot by the group.

Kenya has suffered more than 50 gun, grenade or improvised explosive device (IED) attacks since 2011, when it began its military operation against Al-Shabab in Somalia.

Somali refugees disproportionately affected

Amnesty International argues that while the new law, if enforced, would inevitably lead to refoulement, it could also be discriminatory in its implementation.

“We’re very concerned about who will be targeted to be sent back,” Michelle Kagari, Deputy Regional Director for East Africa at Amnesty International, told IRIN. “We have been documenting that refugees, and Somali refugees in particular, have been disproportionally targeted by the link between refugees, terrorism and Kenya’s security operation in Somalia.”

UNHCR estimates that by the end of 2015, refugees and asylum seekers from Somalia will represent nearly 70 percent of the people of concern to UNHCR in Kenya.

Fears about the targeting of Somalis are echoed within the Somali refugee community.

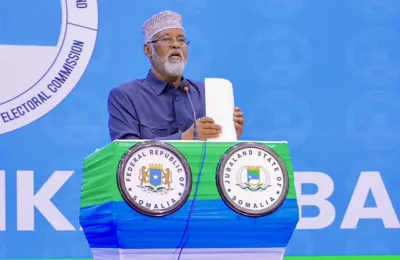

“The anti-terror law is mainly meant for Muslims, and the Somalis in particular,” Sheikh Mohamed Abdi, a Muslim cleric living in Dadaab, the largest complex of refugee camps in Kenya where the majority of refugees are Somali. “There is nowhere to run. We fled from Somalia because of terror-related problems and here, where we thought it was a safe haven, is becoming another hell.”

“There are some refugees who are not registered and staying in the camp and so the police can arrest them, assume they are terrorists and hold them for one year,” said Abdi Ahmed, the Section N chairman in Dadaab, and a community leader. “The entire refugee community lives in panic.” Under the new law, terror suspects can be held for up to one year without trial.

Even registered refugees fear the restrictions on movement that the new law will formalize. “Getting a movement pass these days is very difficult and for students, not having it means missing classes and sometimes exams,” said a Dadaab youth leader, who wished to remain anonymous. He believed that the law will make movement even harder.

The Security Amendment Act comes in the wake of a worsening climate for refugees in Kenya. In April 2014, thousands of ethnic Somalis were rounded up in Nairobi, and held at a sports stadium as part of an operation dubbedUsalama Watch. Similar crackdowns have occurred across the country. Many refugees who had been living in cities were sent to Dadaab.

Government defends law

Kenya’s Attorney General, Githu Muigai, has defended the new law. In his response to the petition filed by the opposition party and various human rights groups, through the Solicitor-General, he said that the discretion accorded to parliament to temporarily increase the numbers of refugees allowed to remain in the country would ensure that refoulement does not occur

He further argued that the laws were necessary to combat terrorism. “We currently have forces in Somalia and it is important to note that the country has been attacked several times. The law, as it is, enables the security personnel to counter threats posed to Kenyans. The issue of life is more important than anything else,” said Muturi.

However, rights groups strongly rebutted this argument. “The government needs to deal with security appropriately and do it in a way that respects human rights. The two are not contradictory,” said Amnesty International’s Kagari. “All three amendments are not only violating the spirit of the constitution but also Kenya’s commitment under the refugee convention.”

Source: IRIN