Almost eight million people face extreme hunger in Somalia and more than 213,000 are at “imminent…

Almost eight million people face extreme hunger in Somalia and more than 213,000 are at “imminent risk of dying” after four failed rainy seasons, according to the UN.

So it should be a relief that after a slow start, over 70% of the UN’s $1.46bn fundraising target for aid has now been reached.

One major humanitarian organisation on the ground tells the BBC it has in fact raised more money than it aimed to.

But it still cannot deliver food, water or cash to many of those who need it the most. The reason, says a senior representative who did not want to be named, is US counterterror legislation.

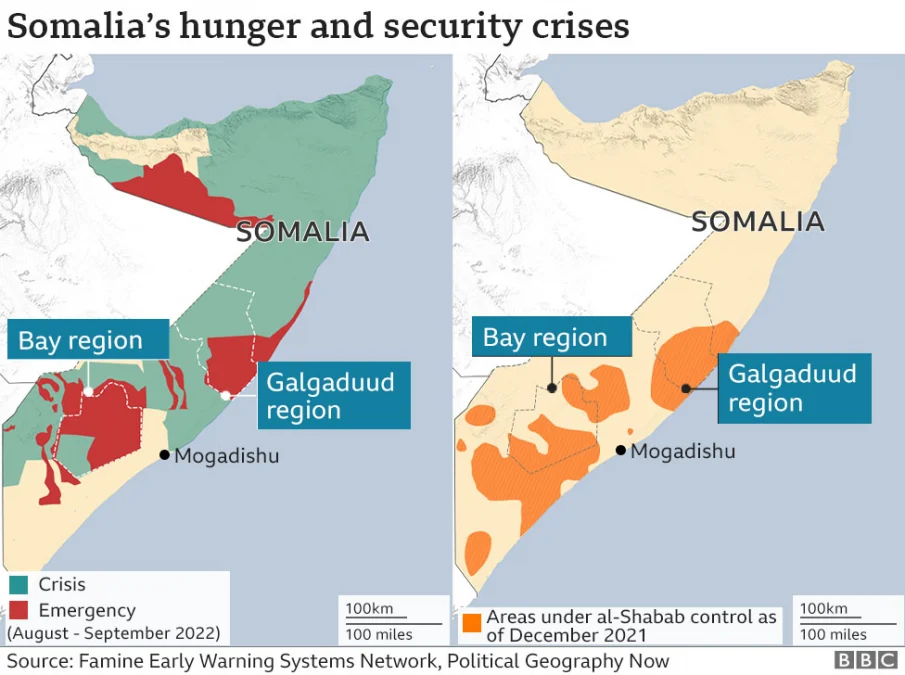

Agencies which get money from the US need to ensure their aid does not fall into the hands of “terrorists” – and large parts of southern Somalia are controlled by al-Shabab, which is affiliated to al-Qaeda and considered a terrorist group by both the US and UK.

“We cannot even move one step,” an official from a second major aid agency tells the BBC, also speaking on condition of anonymity.

Eleven years ago, nearly 260,000 people died in a famine concentrated in al-Shabab territory.

The US says it recognises Somalia’s “grave humanitarian situation” and insists counterterrorism designations are not intended to target aid efforts.

It adds it continuously monitors the impact of sanctions and encourages aid groups to reach out to US authorities for guidance if they are facing difficulties.

But that reassurance does not go far enough for the two groups which spoke to the BBC.

While they are managing to reach government-controlled urban areas, they say supplies are still not getting to areas governed by al-Shabab, home to about 900,000 people, according to a UN estimate.

Some of those are among the areas worst-hit by the drought and may soon face full-blown famine conditions.

The aid organisation that had exceeded its funding goal said the limited provision of aid to Somalia was excused before “as we didn’t have money for a full-scale response”.

But now “uncomfortable questions” were being asked about why more was not being done.

Al-Shabab regularly launches brutal attacks in Somalia and poses a massive obstacle to humanitarian activity.

During the 2011 drought, a UN report found militant commanders were charging aid groups tens of thousands of dollars for access to their areas, had banned some agencies, burned food and medicine and even killed charity workers.

In early September, the militants killed 20 people and destroyed food aid in an attack on several vehicles in central Somalia. Al-Shabab said it was targeting a government-affiliated armed group.

But despite the risks, one aid official asserted that negotiating an agreement with al-Shabab – without fear of prosecution in the US – was a must if they were going to reach vast numbers of people on the brink of famine.

What do US rules say?

As a US-funded humanitarian group, talking to al-Shabab is not banned – but financial transactions are another matter.

Two sets of US federal laws prohibit giving money to al-Shabab:

- sanctions administered by the Treasury

- a law criminalising the provision of “material support or resources” to certain “terrorist” groups, enforced by the Justice Department.

Both affect aid agencies because al-Shabab charges fees at its checkpoints and demands larger, formalised payments of “taxes” in return for access to areas it controls.

In 2011, it was only after famine had already been declared in Somalia that US sanctions were partially relaxed to ease humanitarian efforts.

Treasury officials issued guidance saying food or medicine that “unintentionally” ended up in the hands of al-Shabab would not be a “focus” for sanctions enforcement.

Nor would “unintentional” cash payments – as long as the organisation was unaware it was dealing with the militants.

Aid agencies have said paying “taxes” to al-Shabab is effectively banned.

Treasury guidance advises humanitarian organisations to “consult” sanctions officials if facing such demands.

The ban on giving “material support” to al-Shabab stands regardless of the sanctions – and that has not been loosened.

Both sets of laws are causing a headache for some aid groups, which point to the potential punishments for breaking the rules – fines rising to $1m and up to 20 years’ imprisonment.

US government aid agency USAid – which provides a large portion of Somalia’s aid funds – said Washington had been working with the UN since 2011 to ensure sanctions did not undermine aid work.

But that has not helped the humanitarian officials that spoke to the BBC.

Instead, they are calling for a general relaxation of the rules, to give aid workers confidence to carry out their dangerous but essential work.

“A relaxation would give us more flexibility to reach more areas and it would be timely,” one says.

Thousands of lives are at stake, the other suggests.

Not all US-backed humanitarian agencies report sanctions being an obstacle to their work.

Save the Children’s deputy Somalia country director Binyam Gebru says USAid has been open to helping his organisation find a way of getting aid to hard-to-reach areas.

Negotiations with the militants are being managed through local partners, he adds.

Mr Gebru says that like USAid, Save the Children is “extremely serious” about preventing aid from falling into the wrong hands – taking many precautions and carefully monitoring the delivery of services.

Although that is “restrictive”, he says the agency is still managing to serve militant-governed communities. The main obstacle for Save the Children, he insists, is a lack of funds.

Franz Celestin, head of the UN Migration Agency in Somalia, agrees that US officials are keen to see aid getting to difficult areas – within the existing legal framework.

But ultimately, he believes higher-level negotiations are needed between the UN and al-Shabab to allow agencies blanket access to militant-run areas without the need to pay “taxes”.

In early September, UN humanitarian chief Martin Griffiths told The New Humanitarian that no such talks were ongoing.

What if al-Shabab does get aid cash?

Al-Shabab is already an effective governing force in many parts of Somalia, according to Nisar Majid, visiting fellow at Tufts University and co-author of a book on the 2011 famine.

It is “far more efficient” than the national government at taxing its population and businesses, and has a more robust – if harsh – judicial system, he says.

Through the years, international organisations have felt legal but also reputational pressures to not engage with it – to avoid being exposed in the media as “supporting terrorists”, he adds.

But it is not clear that al-Shabab would gain much of an advantage from aid money, says Abdi Ismail Samatar, geography professor at the University of Minnesota and a lawmaker in Somalia’s upper house.

A 2013 report from the Humanitarian Policy Group said money from aid agencies was only a “small part of a broader system of taxation” by al-Shabab, and the group had “numerous other income systems”.

However, it added that aid comprising tens of thousands of dollars per humanitarian group was still a source of a revenue.

The US believes its rules make it harder for “terrorists” to get funding.

Somalia’s government has declared “all-out” war against the militants and sees shutting down their revenue streams as key to defeating the group.

But an easing of the rules for aid agencies, as well as for services used by emigrants to send money home, would be a “game-changer” for hungry Somalis, says Prof Samatar.

With a fifth consecutive rainy season expected to fail alongside soaring food prices, people’s needs will increase. More aid will need to be delivered to more people.

“We need to save people from perishing before they can be liberated from al-Shabab,” Prof Samatar says. “Fighting terrorists is a long-term project, but saving the lives of starving people is an immediate project.”