Last week the UN Special Representative for Somalia, Nicholas Kay spoke at Chatham House. The talk…

Last week the UN Special Representative for Somalia, Nicholas Kay spoke at Chatham House. The talk was about the country’s successes and the difficulties it faces: the role of the UN mission in Somalia (Unsom) and the “political in-fighting within the government”.

Last week the UN Special Representative for Somalia, Nicholas Kay spoke at Chatham House. The talk was about the country’s successes and the difficulties it faces: the role of the UN mission in Somalia (Unsom) and the “political in-fighting within the government”.

But there’s in-fighting elsewhere that he would have been unlikely to mention: the power struggle between the UN and the current government. It comes down to who should govern Somalia: Somalis or foreigners?

Mr Kay is seen as the most powerful man in the country. He is accused of undermining the government, siding with Somalia’s archenemies, Ethiopia and Kenya, blackmailing and threatening those who oppose him, including the president, and generally using divide-and-rule tactics.

This is a critical year for Somalia. The people have set themselves an ambitious agenda for reform.

Aleem Siddique, Unsom

Responding to the allegations, Aleem Siddique, Unsom spokesperson said: “The United Nations is mandated to support and help co-ordinate international assistance for Somalia’s state and peace building efforts.

“This is a critical year for Somalia. The people have set themselves an ambitious agenda for reform. Unsom is committed to supporting these efforts, guided by the principles of Somali ownership and leadership to restore peace and stability for all Somali people.”

With no functioning central authority caused by the country’s two-decade-long war, most local administrations receive some sort of financial or military support from foreign entities. Therefore, as a matter of fact, non-Somalis have leverage in the country.

‘Yes men’

For instance, the current central government in Mogadishu cannot survive without the backing of the African Union forces, which is part of a UN mission.

Relying on external actors means that, in Somalia, all want to have influence. The main players are the UN, the US, the EU, international NGOs, the African Union, neighbouring countries, Arab nations and Turkey, a relative newcomer.

In public, all of them say they have the same vision, but the reality is that they have their own agendas and interests, which at times collide.

Abukar Arman, a writer and former Somali diplomat thinks the whole problem is that “there is no clear demarcation of executive authority” between top two Somali leaders and also amongst key international bodies.

[Authority in Somalia] boiled down to a game of diplomatic stare-down that sidelines the one who blinks first.

Abukar Arman

“So, it boiled down to a game of diplomatic stare down that sidelines the one who blinks first. Meanwhile, the Somali government functions within said power dynamic and blinks on most occasions.”

But some believe that the current leaders want to look different to their predecessors, whom the Somali public regarded as “yes men”.

The local media often analysis Mr Kay’s appearances, speeches and photo-shoots with foreign players. And people become suspicious when he’s pictured comfortably sitting with Ethiopian or Kenyan leaders, Somalia’s foes.

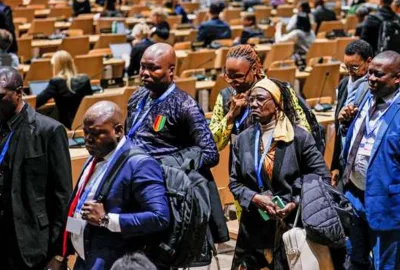

What’s more, Somalis are uneasy with the UN man speaking on behalf of them on international arenas, especially when there is a government that should be playing that role.

Senior government officials told me that they have even considered filing an official complaint against the UN man in the hope of changing him.

‘Decades of bloodshed’

Somalia faces numerous obstacles in its desire to end decades of bloodshed. Some are obvious, others not. Current leaders accept they cannot achieve progress without outside help.

But they would like to claim some sort of ownership of the process. They also feel that the very people who were supposed to support them are sabotaging the system for their own sake.

As Mr Arman puts it, there are “some influential elements – domestic and foreign profiteers – who are hell-bent on keeping business as usual”.

Meanwhile, ordinary Somali citizens who suffer most are holding onto their hope for a better tomorrow. It’s those civilians that decision makers should be thinking about.