A new report presented to the United Nations Security Council on Monday details the threat that…

A

These fighters – whether in small clusters of a few dozen in the mountains of western Tunisia, or up to 3,500 in the Lake Chad region – remain part of the wider network supported by up to $300 million in financial reserves. They’re also funded through oil revenues, a key strategic aspect in Libya, and through kidnapping, illegal mining, trafficking and other organized crime activities.

“Despite the more concealed or locally embedded activities of ISIL cells, its central leadership retains an influence and maintains an intent to generate internationally-directed attacks and thereby still plays an important role in advancing the group’s objectives,” explained Vladimir Voronkov, who heads the UN Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT).

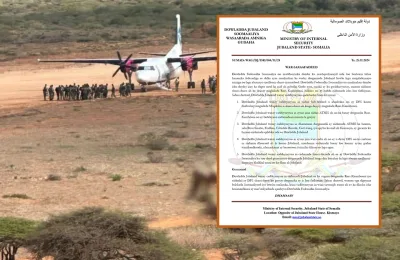

In the Sahel, Islamic State remains less of a threat with smaller numbers than the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam Wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), but the organizations have worked together during some recent attacks. The group has also sustained its presence in Somalia alongside al-Shabaab militants.

Islamic State in West Africa “did not suffer any significant reverse in 2018, and improved its financial position,” the report said. “ISWAP was also able to develop a drone capability, increase the quantity and quality of its propaganda materials, further recruit from the local population and even attract a very small number of foreign terrorist fighters.”

The core of the organization remains in Iraq and Syria, with up to 18,000 fighters remaining in the ranks, including some 3,000 foreign fighters.

The complete UN report is available here.