A country whose very name is almost enough of an introduction, Somalia’s reputation of unfathomable violence…

A country whose very name is almost enough of an introduction, Somalia’s reputation of unfathomable violence and desperate poverty is known around the world. In decades of civil war, it has been described as a “failed state” – a lawless home to gangs of pirates and murderers who terrorise those too impoverished to flee to foreign lands.

A country whose very name is almost enough of an introduction, Somalia’s reputation of unfathomable violence and desperate poverty is known around the world. In decades of civil war, it has been described as a “failed state” – a lawless home to gangs of pirates and murderers who terrorise those too impoverished to flee to foreign lands.

But there is more, so much more, to this land and these people than tales of fear and terror. While no one in this country below the age of 30 has any memory of functioning state institutions – police, schools or garbage disposal – this is a nation that has never given up on the dream of peace and stability.

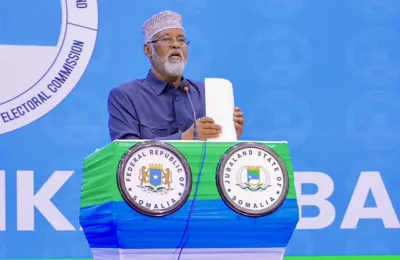

Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed is an economist from southern Somalia. When civil war broke out here in 1991, he sought refuge in Canada, where he became a widely respected analyst for the Bank of Canada, OPEC, and assorted UN agencies.

He had no political experience when, in December 2013, it was announced he would be taking the reins of the east African nation as its new prime minister. He spoke with Al Jazeera’s James Brownsell about his priorities for the country, development, infrastructure – and donors who don’t make good on their promises.

Al Jazeera: You’ve been in this role since December. You’re getting a feel for it, you’re settling in – what do you wish to accomplish during your term in office?

Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed: Well, we want to accomplish our “Vision 2016”, which consists of three milestones. The first milestone is to have the federal states formed; Somalia’s constitution is that of a federal country. The second is to have the constitution reviewed – and that people vote to accept the revised constitution. And the third is to prepare the country for elections.

But as we are doing this, the security conditions must allow this to happen – so we have to reform the security sector. We have to defeat al-Shabab and kick them out of the country, and we have to allow our citizens to feel safe to undertake their normal lives. These are the things we want to accomplish.

AJ: By 2016?

Ahmed: By 2016. This is very ambitious, but we are working very hard.

AJ: You’re an economist, and economists tend to deal with mathematical problems and quite abstract issues – but now you have real-world problems, as opposed to theoretical maths, to deal with. How does your background as an economist help you in your current position?

Ahmed: Well, I am an economist, but I am a development economist, and I have been involved in community work and development. And that allows me to really understand something about how to engage with the people in the community.

If nothing else, politics is about engagement. It allows you to align your objectives with those of the community, and this is what I am doing. So I don’t see a big difference between when an economist is involved in the development of a community and the job of a politician.

AJ: Villa Somalia [the headquarters of the Somali government] has an international reputation for political turmoil and for people not staying in their office for very long. It does seem to be a case of Somalis wanting quick results, even though the change that’s required here is massive. How long do you think you’ll get? How long do you think you’ll last?

Ahmed: For now I plan to stay until 2016, and I hope I will stay until then.

AJ: People want results quickly. Do you think you will be able to deliver tangible results quickly?

Ahmed: We are already delivering some tangible results. In the security sector, we have been able to liberate some major towns – nine major towns have been recovered so far – and we want to continue this process and liberate all the remaining by the end of the year, 2014.

But we are also building institutions. We have confirmed the onward plan for the government’s institutions, which we are implementing and have started work on. We are also doing some mega-political conciliation efforts, and we have been able to achieve major conciliation results among sectors of the community, and we are working very hard to settle questions of the state through the regions. So this is an effort to ensure political inclusivity and the smoothing of relations between certain brethren. And we are achieving good results in this effort.

AJ: Moving on, part of the efforts in reconstruction and security is giving young people alternatives to a life in piracy or al-Shabab. What do you see as the best opportunities for developing those alternative routes?

Ahmed: These alternatives are real. We have a minister dedicated to promoting alternatives and job alternatives for young people. Sports is also another opportunity – a way to spend time wisely, rather than taking the guns and using them. I was in Geneva and we talked about this problem.

AJ: With the ILO [International Labour Organisation]?

Ahmed: Yes, with the ILO – this gives us the opportunity to create jobs for young people, and we are trying to have bilateral arrangements to get some jobs created. We are also using our own resources to create jobs. We have been able to put farmers back to work by helping them clear the land and build irrigation canals. These are the projects we are working on. We are in the process of creating as many jobs as we can.

AJ: How do you seek to develop the infrastructure of the country? You mentioned irrigation channels, but in terms of telecommunications, road building – how do you see that developing over the next few years?

Ahmed: It is very important, but communications is purely a private sector. We have some of the cheapest telecommunications rates in the world, so this is something that is relatively advanced. We plan next to develop flood control infrastructure, building new canals towards the farming lands.

We also have plans to have donors help us. Turkey has been with us with significant improvements to roads in Mogadishu, but we want to extend this beyond the capital to connect the roads to major towns. This is an ongoing process, but we want to see some more results soon.

AJ: Do you find [your efforts are] hampered by donors at conferences pledging billions, but then not seeing the actual money?

Ahmed: This is an issue, and we have had a history of donors making pledges, and the delivery not being impressive – not even satisfactory.

But we also have played our part in the problem, in the past, by not having transparent financial mechanisms. So in the last few months, we have made significant progress in improving our financial governance of development.

We had the council of ministers endorse new directors of the central bank. We have also taken steps to have an auditor general to oversee our national transactions, and an economy based on competition, so we will have some level of competence and integrity to our financial institutions – which we hope will help allow us to attract funds from donors.

So, if we are doing our part, we hope that the donors will also do their part… We are hoping that they will deliver, but we are still waiting.

AJ: You mentioned earlier the federal nation. How do you see the future of federalism developing? Somaliland wants to be treated as its own independent nation, just to give the example of one region. How do you see the future of federalism in Somalia?

Ahmed: Federalism is inherent in Somali culture. Somalis have always been independent-minded and through centuries have wanted to manage their own affairs. Now Juba and Puntland are getting greater autonomy and we hope other regions will follow soon. My government supports this, and we hope that full federalism will happen – it should happen, as part of the 2016 plan.

AJ: Going back to the donors – what’s your message to the international community?

Ahmed: My message is this: Deliver on your promises. Number two, trust the government and empower the government to manage donor resources in cooperation with you.

What we have is this: Money for Somalia is spent in Somalia, but we don’t know how it happens – it happens through NGOs and ways that are hidden, or at least that are invisible to us.

So we want donors to work closely with us and empower the government, and be accountable to the development process of this country. We are accountable to the people, and we want to be partners with the donors.

We want to be able to set priorities and the way in which we implement the projects, so that those priorities are based on the real needs – so we are spending the resources as effectively as possible. Aid effectiveness is something we want to see happen, from priorities to implementation to monitoring. This is what we want the donors to consider.

Follow James Brownsell on Twitter: @JamesBrownsell