Earlier this month, Somalia’s Attorney General filed a case against Kenya at the International Court of…

Earlier this month, Somalia’s Attorney General filed a case against Kenya at the International Court of Justice in The Hague over the maritime border dispute, which has been going on for the past at least six years.

It was August last year when Somalia asked ICJ to determine the maritime boundary between the two nations in a row that could decide the fate of potentially lucrative oil and gas reserves off the East African coast.

The Court is, however, expected to give its final ruling on the dispute by 2017.

The continent of Africa is no stranger to conflicts and disputes over natural resources. The diamond conflicts in Angola in the 1980s; Sierra Leone (1990s) and the recent Niger Delta oil and gas conflicts in Nigeria are few examples of how resources have deadly fuelled conflicts in the continent.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Eritrea and Ethiopia fought brutal wars over land and territories. Libya and Chad also battled each other for similar reasons. Botswana and Namibia fought over the Kasikili Island or Sedudu Island in the Chober River. The dispute was peacefully settled in 1999 by the International Court of Justice. Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya have had their fair share of border disputes and conflicts.

Global interest for the richness of the Western Indian Ocean has risen over the past decade, affecting the hydrocarbon resources and fish sector in East Africa.

Kenya wants the border ought to run along the latitudes of the Indian Ocean similar to how its border with Tanzania is aligned, giving it more sea territory. However, Somalia wants the boundary to run perpendicular with the coast.

The Kenya-Somalia dispute is over resources within and beneath the ocean floor. Unstated in the dispute is the desire to licence oil/mineral prospecting firms and the revenue that will come with the potential discoveries.

In 2009, Kenya and Somalia signed a memorandum of understanding that the border would run east along the line of latitude, but Somalia, which has lacked an effective central government since 1991, then rejected the agreement in parliament.

By prompting Somalia to enter into the MoU with it in 2009, Kenya was trying to meet a May 2009 deadline set by the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLOS), which required countries to submit agreements with neighbouring states on the limits and orientations of their maritime boundaries.

For Kenya, the MOU had settled matters once and for all. Nairobi officials believe that the April 2009 agreement signed by then-Kenyan Foreign Affairs Minister Moses Wetangula, and his former Somali counterpart, Abdirahman Warsame, allowed Kenya – not Somalia – to officially demarcate its maritime borders to include the approximately 200 nautical miles off the coast of the Horn of Africa. More precisely, for Nairobi authorities, the MOU extended the Kenyan boundary east to approximately the 45° line of latitude.

UNCLOS asks states with shared coastlines to agree on the extents of three different areas – their territorial seas, exclusive economic zones and continental shelves. Launched in 1982 and signed by 130 countries by 1994, UNCLOS seeks to establish the sea limits and sovereignty of states on the use of the sea and allows coastal countries to seek an extension of their exclusive economic zones beyond the 200 nautical-mile’ limit.

Somalia’s Transitional Federal Parliament (TFP) on August 1, 2009 unanimously rejected the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Kenya which suggested there was a disputed zone in a territorial sea belonged to Somalia. The TFP also rejected any subsequent future demarcation and delimitation talks with any state including Kenya.

Somalia gained its independence and joined the United Nations before Kenya. Somalia celebrated 55 years of Independence this year; many citizens are asking themselves why such a dispute has come at this time on its maritime boundaries?

Despite the generally good relationship between Kenya and Somalia, there have been concerns that if these political tensions between the two countries are not resolved, they could escalate and culminate in a war.

However, many Somali citizens have raised questions of whether it was the suitable time for the Federal government to take Kenya to the court on this issue.

Type of Government

The current members of the Federal Parliament came through selection from their clan elders, not elected from the communities they hail from. They later on voted a President who appointed a Prime Minister, then approved by the Parliament and later on forms the cabinet squad.

However, the Somali government is not eligible to represent the Somali people on such cases since it did not come to power through one person, one vote formula.

In the 2009 decision by the Transitional Federal Parliament, it was clearly stated that a government that comes through Parliamentary elections has no the right to represent the nation on the maritime dispute.

Challenges & Current situation

Somalia is a country that has experienced excessive amounts of political instability during the past two decades.

After several transitional Somali governments failed to re-establish control over the country, Somalia created in 2012 the Federal Government of Somalia under President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, who remains the current leader. While Somalia has made considerable progress, it faces severe political, security, economic, and humanitarian challenges.

According to many experts, it is not the right time to challenge a long-standing government in an international court and has already troops in the country fighting the government’s enemy. Many believe that if Somalia had regained its strength, Kenya wouldn’t have made any sea territory claims.

Former Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi once said that some of the countries neighbouring Somalia, feared that united and prosperous Somalia might pursue its “expansionist dreams”, and claim the territories including the North-Eastern Kenya province.

In preparing its case, Kenya reached out to a wide range of diplomats, politicians, and scholars to build domestic and international support for their claims. It has been confirmed also that it has hired Foreign International law experts to help defend its claims.

Lack of consultations

The sea dispute case was submitted to the International Court of Justice without making consultations with the Somali civil societies.

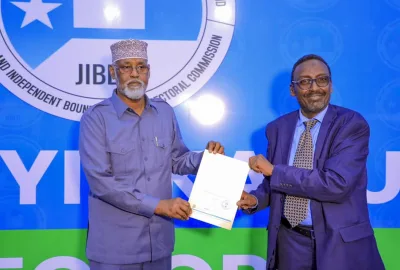

Earlier this year, Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf, a Somali citizen, was elected vice-president of International Court of Justice. According to credible sources, the Somali government did not reach the International law expert to seek for suggestions on the case of this dispute.

This has brought doubts on whether the Somali government in secretly assisting the Kenyan government to win the case.

For Somalia, the fight over the maritime demarcation goes far deeper than a quest for seaside riches. It is also a matter of pride. The view among many Somalis is that their country has been taken advantage of, not only by Kenya, but by international firms which they have accused of capitalising on their decades-long lack of central government for their own financial gain.

Weak Case

Experts in law who have seen the 150-pages case submitted have told Horseed Media that the case is weak and not strong enough for Somalia to win it in the end. One expert said that it is lacking the history of the Somalia maritime boundaries and has been indicated in the case that the dispute has been going on for decades.

Other sources have said that the current Federal government wrote that the territorial waters are only 12 nautical mails contrary to law No. 37 of September 10, 1972 which states Somalia’s territorial sea is by breadth 200 nautical miles.

If the court opens the hearing of the case, Somalia cannot withdraw nor appeal from the original case submitted.

If such an event were to pass, however, Kenya is believed to have the upper hand. Nairobi has already secured enough powerful allies, including Norway, France and the US (all of which have a stake in the Kenyan-authorised offshore oil blocks), that would conceivably make a Kenyan victory a ‘sure thing’ from the start.

With such challenges facing the Federal government, will the Somali people wait and see ruling of the court? And support their UN-backed weak government in both win-lose scenario or put pressure on it to withdraw the case from the court?

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations (UN) and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) is a specialist international tribunal to decide on disputes arising out of the interpretation and application of the Convention. However, it doesn’t have the legal authority to rule Somalia’s waters in favour to others, which if happens, could be regarded as ‘’Sea Piracy’’.

Horseed Media